“If you told me last year that I would be giving my dog shots of fluid every day, I would have said you were crazy,” comments Cathy Park of Worcester, Massachusetts. “I’m very needle phobic.” But injecting her 10-year-old white Lab, Bunson, is exactly what Ms. Park does each evening. Bunson is in the advanced stages of chronic kidney failure and can no longer drink enough water to compensate for the amount he urinates.

Administering a daily injection of fluid is allowing him not only to stay alive but also to have quality of life. “He’s actually a little perkier,” Ms. Park relates. “He likes to go for a ride in the car and hang his head out the window.” Before, he had so little energy he was drooping.

Bunson’s doctor, Tufts veterinarian Armelle de Laforcade, DVM, isn’t surprised that Ms. Park has gotten the hang of sticking Bunson with a needle every day. “There are some people you talk to,” she says, “and explain that their dog has a disease that requires injections, and they say, ‘I can’t do that. I can’t deal with needles.’ In those instances, people might adopt out their pet or choose euthanasia. But usually,” Dr. de Laforcade explains, “even squeamish people can learn how to do it.

“People who think they couldn’t go near a needle, once they try it, they realize it’s not that bad — especially if you give a treat afterwards. For those dogs who are food driven, they don’t mind the shot in the first place, and they look forward tothe treat.”

It’s true. Dogs themselves don’t have needle phobias, so they don’t fear the injections and thereby make it difficult to administer them. They may flinch initially, especially if they’re puppies, but they get over it very quickly. A big reason for that is that the shots are subcutaneous — given under the skin rather than directly into muscle or other tough tissue — and are therefore less painful. That makes the whole process simpler.

The 3 Main Reasons Dogs Get IV Shots At-Home

There are a number of reasons someone might have to give a dog shots at home. For instance, an owner whose dog has arthritis might be taught by a veterinarian how to inject adequan, a joint supplement that’s often more effective than, say, glucosamine. But three conditions account for most of the instances in which people end up becoming their pets’ home health nurses.

1. Chronic Kidney Failure

“The body is 70 percent water,” explains Dr. de Laforcade. “And the major job of the kidneys is to get rid of waste but hold onto as much water as possible.” If the kidneys start to fail, a dog will drink more to make up for loss of water through the kidneys. But after a while, the extra drinking will no longer compensate for the kidneys’ compromised ability. That’s when a dog might require injections of fluid at home, as in Bunson’s case.

“He was becoming severely dehydrated,” Ms. Park says. “I was trying to get water into him with a syringe,” but that wasn’t enough. At first, she took him to Tufts every other day to have the fluid injected, but the visits were becoming expensive and inconvenient. Also, every other day proved not to be enough for Bunson’s needs. He eventually required an injection of fluid every single day to keep pace with the amount of fluid he was urinating.

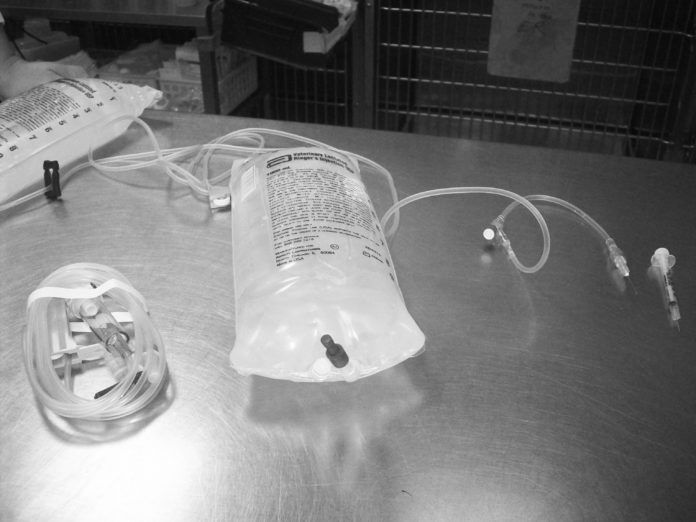

That’s why Dr. de Laforcade demonstrated to Ms. Park how to inject the fluid herself. “Pretty much anywhere on the body is good,” the veterinarian says, “but between the shoulder blades on the back of the neck works particularly well. There’s a lot of loose skin there. We tell clients to pinch the skin in a shape sort of like a tent — like an upside down ‘V.’ Then you put the needle through the base of the tent’s ‘front flap.’ If you go too near the top, you could potentially send the needle out through the other side rather than keep it in the body.

“It’s no big deal,” Dr. de Laforcade says. “It just feels like you’re poking a bag. Some people start out saying, ‘I’m going to faint,’ but they learn how to do it. We have them start with a syringe of saline, then switch to the medicine.” [The fluid is “medicine” because it’s not tap water, which could burst a dog’s red blood cells. It contains specific concentrations of electrolytes like sodium and potassium to mimic what’s already inside the dog’s body.]

Says Ms. Park, “the doctor showed me how to do it right on Bunson. It was hard at first. I don’t even watch needles going into me. I keep my eyes closed. But you know, they’reyour baby.”

The liter of fluid that Bunson receives each evening takes about 10 minutes to go in completely. It makes its way to the needle from a bag that hangs from a hook above the dog. “We get Bunson all comfy on his bed,” Ms. Park says, and “lay down with him or just sit with him, massaging his little shoulders and petting his nose. Sometimes he’ll lay on my lap with his head on a pillow and go to sleep while the fluid enters his body. He doesn’t fight it at all.”

Ms. Park is aware that her time with Bunson is limited. When a dog’s kidney disease is advanced enough that he requires fluids every single day (many people start out needing to inject their dogs with fluid only once or twice a week), the prognosis is very guarded. “We know we could have a turn for the worse any minute,” she says. “It’s something that will only get worse, not better. And everyone has his time.

“But he’s definitely in better shape right now. His numbers are stable. He still keeps perking up and wanting to do doggie things.”

2. Canine Diabetes

Unlike with people, there is never an option for dogs with diabetes to take a pill in order to bring blood sugar levels into line. Once diabetes is diagnosed, insulin injections are necessary to keep the dog alive.

The good news: With insulin, a dog with diabetes can live a wonderful life for many years. And the amount of insulin injected is tiny compared to the amount of fluid injected into a dog with kidney failure. You do have to give insulin injections twice a day rather than once a day, as is the case with fluids for kidney failure. But you don’t have to wait 5 to 10 minutes for the fluid to leave a bag and enter the body. Furthermore, the needle is much smaller than it is for injecting fluid into a dog with kidney disease — tiny, really — making it easier for people who are needle phobic.

If a Tufts client is very scared, we start by having the person inject an empty plastic bag, or perhaps the skin of an orange, but most people are able to go right to injecting their pet. For dogs who need a little numbing at the site — and most dogs do not — a hard pinch or several seconds with an ice cube applied to the skin does the trick. As with kidney disease, the easiest site to give the subcutaneous injections is between the shoulder blades. The owner makes the same “tent” out of the skin.

A much bigger issue with insulin injections than the injections themselves is the commitment it takes to make sure your dog gets the shot at 12-hour intervals without fail. If you leave your dog with a pet sitter, the pet sitter has to learn how to give the medicine. If you go on vacation, the people where you board your pet have to be able to take over. You also need to make sure you always have enough insulin on hand. We can’t tell you the number of clients who call us on Christmas Eve to say they don’t have a sufficient amount to make it through the holiday. Sometimes you can get the prescription filled at your local chain drug store, but if your dog uses mail-order insulin only, falling short can create a big problem. The formulations may differ from source to source, and it may not be possible to switch back and forth.

Note: Because of the way syringes are marked, it’s all too easy to give a tenfold overdose of insulin — perhaps 50 units instead of five. Furthermore, the difference between those two amounts comes to less than a tenth of a teaspoon, so you can’t eyeball it. It’s not a problem once you get used to the process, but it does require paying very close attention.

3. When Dogs Need Blood Thinning Treatment

In people, says Dr. de Laforcade, “the most common blood thinner used is probably warfarin, also called Coumadin. But warfarin takes a lot of monitoring. Someone taking it has to keep going to the doctor to have his blood levels checked because absorption is variable. In addition, different foods that people eat can interfere with the drug’s action. For dog owners, frequent visits to the veterinarian for blood monitoring would prove onerous, not to mention expensive.

For that reason, dogs who need blood thinning, most often because they are prone to clots, are given heparin, which gets injected under the skin — again, most easily in a “tent” between the shoulder blades. Sometimes dogs are given the drug for a defined period, perhaps two or three weeks. Other times, it’s a long-term, twice-a-day protocol, but somewhat more forgiving than the diabetes protocol about being an hour off here or there. Either way, like fluids for dogs with kidney disease and insulin for dogs with diabetes, it saves dogs’ lives.

Whatever the reason for the injections, Cathy Park knows the benefits. “I could see the difference in Bunson as soon as I started,” she relates. “It makes you glad to be able to do it. While he has quality of life, I’ll keep with it. Whatever’s in his best interest.”