It was the perfect pet storm. Danielle and Matt Buczek were about to leave for a long-awaited vacation in the Caribbean when their 13-year-old chocolate Lab, Coco, developed an ulcer on her eye that required drops three times a day. She also had to wear a cone to keep her from pawing at her eyeball. “Her eye wasn’t working right, and we didn’t even know at first if it was an ulcer that was the problem,” says Mrs. Buczek. Although the couple very much trusted their dog sitter, they hated having to leave the eye drop administration to her and wished they could be home to see whether Coco’s condition improved or worsened.

“Maybe like halfway through our vacation — we’re getting ready to go out to dinner — my husband gets an e-mail from his father,” says Mrs. Buczek.

The dog sitter was taking Coco to the hospital at Tufts. But it wasn’t about her eye. “She hadn’t had a bowel movement in days and didn’t seem to want to urinate. She also had a hard time walking. We were, ‘Oh my God, what’s wrong with her?'” Mrs. Buczek relates.

The Buczeks had had their phone service turned off because it’s expensive to talk to people in the States from the Caribbean, “but we had to turn it on so we could communicate with the doctors,” says Mrs. Buczek. “E-mail can only get you so far.

“We didn’t know anything for maybe 18 hours. They needed to run tests, try to figure out what was wrong. Because Coco has a long history of kidney disease, she has a very thick case file. The folks at the hospital were working to sort through her medical history to figure out what could be the problem while they were getting all the tests done. Those first 18 hours were very scary.

“Finally, one of the doctors called us and said most of the values were in the same range as in her last check-up.” They did find some things that stood out, though, and needed immediate attention.

The doctor who phoned the Buczeks was Daniel Jardes, DVM. “Coco’s signs were kind of hard to interpret,” he told Your Dog, “because she was being watched by a baby sitter” who wasn’t familiar enough with her baseline behavior. However, it was clear that “her energy was off,” he noted. By the time she reached the hospital, she was so weak she couldn’t walk well, and she also couldn’t get up easily. She was having a rough time. Still, Dr. Jardes said, “she was a very sweet dog, Her tail was going the entire time, and she was extremely personable, even though she felt sick. She was a sweetheart, not crotchetyand cranky.”

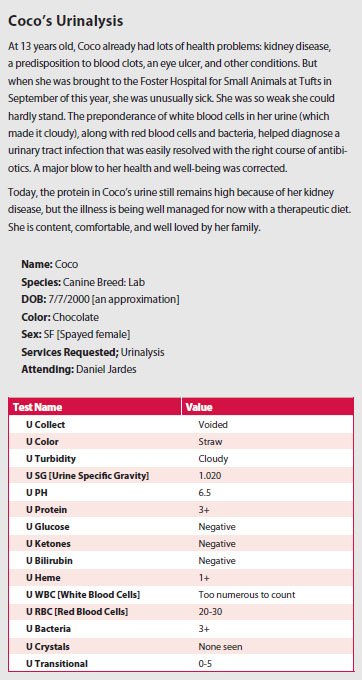

One of the tests that helped pin down her condition was a urinalysis. “When we collect a urine sample,” says Tufts veterinarian Linda Ross, DVM, an expert on the urinary tract, “it primarily gives us information about the urinary tract and kidney function. It’s best used in conjunction with blood tests — the complete blood count and the chemistry profile. Together, the urinalysis and those two tests paint the clearest picture for the veterinarian.”

How to ‘catch’ the urine

There are three ways to collect urine.

Voided, or free catch, sample: The owner, or a veterinary technician, literally follows the dog around with a little cup or pan. When the dog is getting ready to void, the person sticks the pan under the animal and collects the urine. “It’s easier in male dogs,” Dr. Ross says. “Females squat so low. But it can be tricky either way because the dog doesn’t understand why you’re running up to him while he’s urinating and will stop in the middle and run away.”

There’s also a problem from a medical standpoint. For a female dog, the opening of the urethra is inside the vaginal area and in a male, the prepuce (foreskin) of the penis. That is, the urine flow starts inside the body, and so the vet ends up with material that was in the vagina or prepuce at the same time that she gets the urine. That can make diagnosis more difficult. “If you’re looking for an infection,” Dr. Ross says, “you may not know whether you’re seeing bacteria that are normally supposed to be in the vagina or prepuce or bacteria that are in the urine but shouldn’t be.” For that reason, it may be better to obtain a sterile urine sample, even though it’s more invasive for the dog. There are two ways to get a sterile urine sample.

Sample obtained with a urinary catheter: This is not very difficult for most male dogs but can be quite difficult and often requires sedation in females. Occasionally, a female dog may even need anesthesia.

Sample obtained via cystocentesis: This procedure involves inserting a needle in the bladder by way of the abdomen and withdrawing some urine. “It sounds terribly invasive,” Dr. Ross says, “but for the most part it’s quick and non-painful,” far less painful than catheterization, especially for a female. It’s what we do most of the time to get a urine sample. We strongly recommend it, in part because you know for sure that it will be a sterile sample. Even a catheter is not 100 percent foolproof. It still has to pass through the vagina or prepuce and can pick up bacteria and other material from inside the body.

At the lab

Once the urine sample has been obtained, it’s sent to the lab for analysis. Here’s what they look at.

Appearance

Color. At first, the laboratory technician will simply look at the urine and note what color it is: pale yellow, yellow, dark yellow, or, if there’s blood in it, red or brown. (Older blood might look brown as the red blood cells will have broken down more.) Pale yellow, sometimes noted as “straw,” generally means the concentration of the urine is at an appropriate level.

Turbidity. The tech will also look to see whether the urine sample is clear or cloudy, whether s/he can see particles in it. The fact that Coco’s urine was cloudy (see the chart on page 7) was a reflection of “all the white blood cells in her urine,” says Dr. Jardes. As the chart notes further down, the number of white blood cells were “too numerous to count.”

Specific Gravity

USG. “USG” stands for the urine’s specific gravity, which is a numeric way to tell how concentrated the urine is. For dogs, says Dr. Ross, kidneys that function well can concentrate the urine to greater than 1030, which will appear as 1.030 on the urinalysis.

“If we get only a tiny bit of urine, the specific gravity is the single thing we’ll test for,” Dr. Ross says, “because it literally takes one drop of urine to do it.”

Coco’s specific gravity was a little low, but “that was tough to interpret,” Dr. Jardes says, “because she was on IV fluids at the time. She may just have been very hydrated as opposed to not being able to concentrate her urine.”

Dipstick Analysis

What follows in this section falls under the heading of the dipstick analysis. “We literally take a little plastic strip that’s about inch by 3 inches,” Dr. Ross says, “and dip it into the urine. Attached to the strip are little paper squares that are about inch on each side. And each has a certain chemical in it that will change color depending on what’s being tested for and what is found.”

U pH. This tells the pH of the urine — how acidic or basic it is. Many dogs have acidic urine (below 7), “and that doesn’t bother us very much,” Dr. Ross says. That was the case with Coco.

Protein. The best amount of protein is none, or a trace. “When you get more than that,” Dr. Ross says, “it can signify certain types of kidney disease, or just kidney damage, or an infection. If we see a lot of protein in the urine — the highest number is 4+ — that will definitely lead us to do further evaluation.

The fact that Coco’s protein value was 3+ was no surprise. She had already been treated for chronic kidney disease for years.

Glucose. You don’t want any sugar in the urine, so the glucose level should be negative. If the vet sees any, that would lead to a check of blood sugar for diabetes. “You might also use a positive number to reassess the amount of insulin you’re giving a dog who already has been diagnosed with diabetes,” Dr. Ross points out.

Ketones. A byproduct of glucose metabolism, ketone levels will also indicate whether a dog is diabetic. When a dog becomes severely ill with diabetes and her blood sugar is not under control, high levels of ketones in the urine may appear. Anything other than “negative” for a ketone value is not good.

Bilirubin. Since bilirubin is a breakdown product of the hemoglobin in red blood cells and is processed by the liver, any value other than “negative” can indicate a) that the dog may be losing or breaking down too much blood and is anemic or b) that she has liver disease. But a small amount of bilirubin in the urine can also be normal (1+ to 2+, depending upon how concentrated the urine is).

Heme Protein. On some urinalysis write-ups, this is called “hemoglobin,” and it can mean that there’s too much red blood cell breakdown — not good — or that some red blood cells in the urine broke down after they were sitting there for a while. In such a case, it may not be significant if there’s only a small amount. There’s no specific cutoff that veterinarians look for.”Heme protein has to be assessed in conjunction with blood tests,” says Dr. Ross. “If blood tests show there’s too much loss of red blood cells, it’s definitely something you want to investigate further.”

Dr. Jardes did not like seeing a heme protein value of 1+ in Coco. He said the red blood cell breakdown it indicated went along with Coco’s problem.

Sediment

Once the dipstick part of the urinalysis is complete, the urine sample is spun down in a centrifuge, and the liquid at the top is discarded. The material left at the bottom is called sediment. The veterinarian puts some on a slide and looks at it under a microscope. Here’s what she sees.

WBC. WBC stands for “white blood cells,” and if the vet sees any, it could be a sign of infection or inflammation because white blood cells are involved in fighting both. The caveat is that if it’s a free-catch sample rather than one taken by the doctor, the presence of white blood cells is hard to interpret because they could have come from the prepuce or vagina. A second urinalysis performed on a urine sample obtained with needle may be necessary. Coco’s urine was obtained via a naturally voided sample, but even so, Dr. Jardes felt that because the white blood cells were “too numerous to count,” it seemed evident that an infection was present.

RBC. Red blood cells in the urine might indicate bleeding into the urinary tract, which can be the result of an infection or stones rubbing on the wall of the bladder or a urinary tract tumor. But there’s the same caveat with seeing red blood cells in the urine as with white. A few might be present because of the way the urine sample was obtained. A second urine sample may be necessary to help interpret the findings. In Coco’s case, Dr. Jardes felt the high red blood cell count was consistent with an infection, specifically, with “some bleeding associated with inflammation,” he says.

Bacteria. You know the drill. Bacteria could indicate an infection, or, if the sample was voided rather than taken in the vet’s office, simply the presence of some bacteria in the prepuce or vaginal area. Because of the high red and white blood cell counts, the presence of bacteria in Coco’s case helped strengthen the case for an infection.

Crystals. Crystals are seen when minerals have precipitated out in the urine. Sometimes, in small numbers the presence of certain types, such as struvite or calcium oxalate crystals, can be normal. “The ones that almost always indicate something abnormal is going on are urate or cystine crystals,” Dr. Ross says. “Urate stones form when there’s too much uric acid in the urine as the result of certain kinds of liver disease, for example, or the relatively frequent inability of breeds like Dalmatians and English bulldogs to process protein properly. Cystine crystals tend to form in the urine of other breeds who can’t properly metabolize cystine properly, namely Newfoundlands and corgis. The genetic defect can’t be fixed, but owners can at least be warned about the possibility of stones.

Transitional. “This is a type of epithelial cell that gives the bladder its properties,” Dr. Jardes explains. Coco’s having some in her urine indicates that there has been some shedding of those cells, which you see with inflammation.

Update on Coco

It turns out Coco had a urinary tract infection, or UTI, that got rather far before it was caught. “We have a fenced-in backyard, so she can kind of come and go when she wants,” says Mrs. Buczek, “and you don’t always immediately notice if she’s urinating more frequently or less frequently or straining to ‘go.’ It was even harder for the dog sitter,” who didn’t know Coco’s habits as well as the Buczeks did.

Dr. Jardes suspected a UTI before he even ran any tests. “She was taken outside to urinate at the hospital,” he says, “and the technician who walked her noted that her urine was malodorous, quite pungent” — a sign of infection.

When her urine and blood work helped confirm his suspicion, he put her on a course of antibiotics. “She has been doing nicely since we started the medication,” he says.

Mrs. Buczek would agree. “By the time we arrived back home she was better than when she was at the hospital,” she says, “but she was not the dog we had left a week earlier. She was still really weak. It took a few more days of letting the medicine do its work, of having us there, until she was finally back to her normal self.” Today, the 13-year-old is happy, relatively healthy, and no doubt looking forward to the holidays.

This is the last in a three-part series on basic lab tests.