When pitbull mix Brooklyn came to live with Rochelle Lucas and Aaron Roylance at the ripe age of 9, he tipped the scales somewhere between 90 and 95 pounds. “The vet said, ‘he cannot stay at this weight,'” Ms. Lucas recalls. “‘That’s going to be really hard on his joints.'”

It was true. “He could sprint a little,” Ms. Lucas says, “but he got tired very quickly. He couldn’t sustain play.”

So the Rio Rancho, New Mexico, couple put him on a weight management plan — no more fatty burgers, like his previous owner had given him, and a more regular feeding schedule with real dog kibble — and he dropped 15 pounds. That’s when the trouble began.

“One fateful trip to the dog park,” Ms. Lucas relates, “on the heels of his coming off his weight loss and being able to function like a regular dog, running around and having a good time, he started limping as we were getting ready to leave.”

It turned out the newfound spring in Brooklyn’s step led to a torn cranial cruciate ligament in his knee — the equivalent of a torn ACL in people. He ended up having to have two surgeries because the “fishing line” the veterinary surgeon first placed in his knee to restore range of motion wasn’t strong enough and broke. All that down time from the two operations made him even more out of shape than he had been. He was trimmer, yes, but unconditioned after all those years of becoming a rolly polly. He didn’t even want to put the paw of his affected leg on the floor. Post-surgery, he couldn’t bear weight on that limb without pain and was “kind of hopping around on three legs,” as Ms. Lucas puts it.

Enter physical therapy

To help Brooklyn get back on his feet, or foot, and not let the muscles in the affected leg atrophy even further after his surgical intervention, Ms. Lucas and Mr. Roylance took Brooklyn to see veterinarian Laura Hady, DVM, of Canine Physical Rehabilitation in Albuquerque. With certification in canine rehabilitation, she has been seeing him for rehab/physical therapy once a week and sending the dedicated couple home with exercises to do with Brooklyn between visits. The doctor even films the exercises Brooklyn is supposed to do so his “parents” have a visual reference they can use while working with him.

The sessions are conducted similar to the way a person would exercise, Ms. Lucas says, with warm-ups, actual exercises, and cool-downs. And the exercises are both passive, where Brooklyn has his leg stretched in different ways by his owners, and active, where he has to perform the activities himself.

How do they get him to perform physical reps and sets that use a limb that causes him pain? “We ply him with lot of treats and praise,” Ms. Lucas says. “They do the same things during the appointments.” You often have to coax a dog into doing the moves that will restore his mobility.

What’s entailed in the exercises

Warm-up begins with a massage to get the muscles going. The muscles start out “cold and tight,” Ms. Lucas says, and need to relax a little. “Then we have some stretches we do to keep the leg moving as the scar tissue grows back in.” The stretches the couple performs on Brooklyn make it easer for him to move on to the exercises he has to perform for himself.

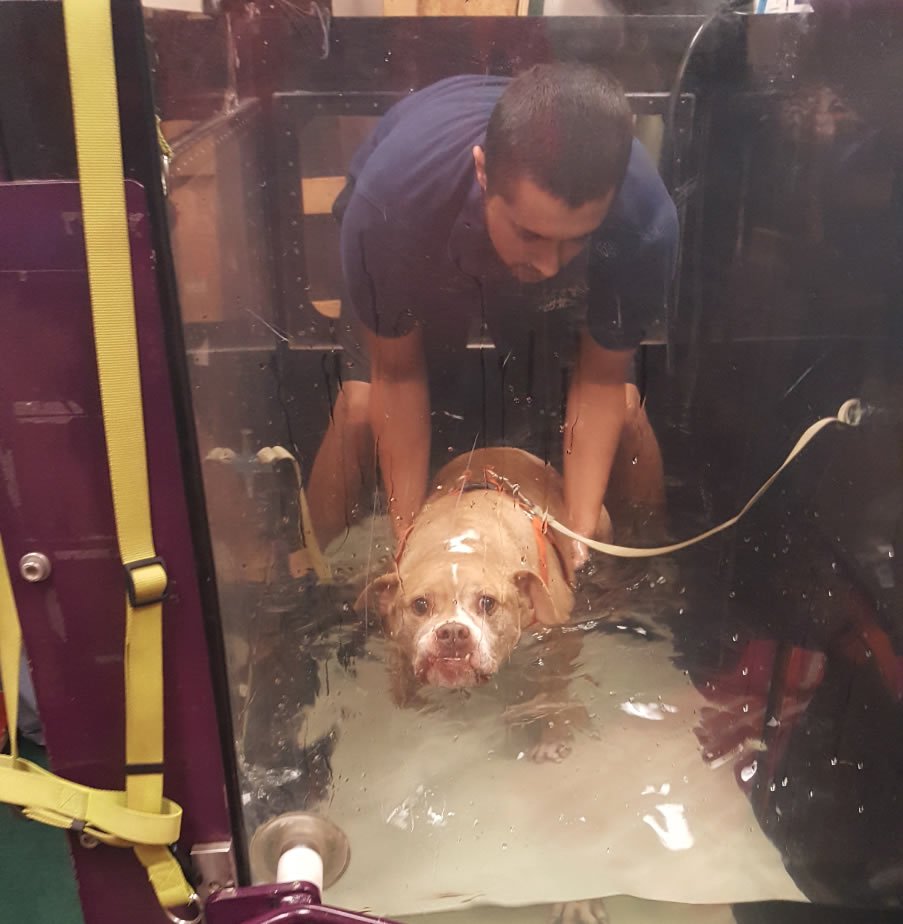

What are those exercises? Some days Brooklyn has to walk on an underwater treadmill. His head is above water, but walking in water allows him to work toward regaining mobility with little to no jolting impact.

We also “kind of intentionally put him off center so he’s forced to use his leg to steady himself,” Ms. Lucas says. How?

One way is with a small child’s trampoline that Dr. Hady sent the couple home with. Brooklyn has to walk onto a pillow, from the pillow onto the trampoline, where he stays for 10 seconds, and then off the trampoline and back onto the pillow before reaching the floor. The steps “leave him off kilter, and that forces him to engage all four legs,” Ms. Lucas says. “He’s off balance from start to finish. We just do three to five reps. Some days hejust won’t.”

Another exercise involves “crossing the train tracks.” Ms. Lucas and Mr. Roylance set up scraps of wood in a line, and Brooklyn then has to walk over them without touching them. “We put them a certain distance apart so he can’t just leap over them,” Ms. Lucas says. “He’s forced to pay attention and navigate them if he doesn’t want to step on them. In doing so, to keep his balance, he uses that leg to help him stay upright.”

The couple does the exercise sessions with Brooklyn every day. “Optimally, it’s twice a day,” Ms. Lucas says. “But given the way life goes and our work schedules, we usually get in one good session for the day.”

Is the physical therapy helping? “Definitely,” Ms. Lucas says. “He is able to bear more weight on that leg. It’s a slow process. He is not fully walking on it yet, but we have started seeing him play with our other dog again. He had stopped doing that after the surgery. He was probably worried he’d get knocked down.”

The leg “doesn’t stay down all the way,” Ms. Lucas adds, “but he is attempting to stretch it. When he’s walking short distances, he’ll attempt to put it down. She believes he’s “going to be able to make a full recovery.”

Is rehab or physical therapy right for your dog?

Successful recovery from an operation is just one reason a dog might benefit from physical therapy. It could also be helpful for dogs with arthritis and other conditions that cause joint pain or impairment of movement. Says Woburn, Massachusetts-based veterinary surgeon Cara Blake, DVM, DACVS, who has certification in canine rehab, many dogs “are grossly overweight. You want them to get up and moving. It’s just like going to a trainer. You work on the core, build up muscle [and help them burn calories].

“A lot of older dogs,” she adds, “just like humans, lose muscle mass and gain fat. The dog loses mobility, becomes painful, and doesn’t want to move. If you can get a geriatric patient up and mobile, they’ll be willing to move around, then they’ll build their muscle strength. So if we can maintain their muscle mass, and potentially get some weight off for those arthritic patients, it’s a tremendous amount of help in terms of increasing mobility and decreasing pain.”

Consider that one of the reasons range of motion deteriorates for a dog in pain is that his muscles at the affected spot atrophy. But physical therapy in the form of strength training, also known as resistance training, stems the loss of muscle by repeatedly working the muscles to keep them whole and capable of action. The better the shape the muscles are in, the more they’ll be able to absorb the brunt of impact, sparing the joints from having to do so.

Both veterinarians and veterinary technicians certified in canine rehab know how to manipulate a dog’s muscles with passive exercises as well as how far to push him with active ones that he must do on his own so that he can regain strength and motion without risking further injury. The field was started by physical therapists for people who had an interest in veterinary medicine. They applied physical therapy to animals they knew personally, and the field burgeoned from there.

Training and certification is offered at only two sites: the Canine Rehabilitation Institute in Wellington, Florida (which lists certified practitioners by state at caninerehabinstitute.com),

and the University of Tennessee (utvetce.com). Both provide training for veterinarians and veterinary technicians (nurses), although technicians cannot offer physical therapy except under a veterinarian’s supervision. They cannot hang a “canine rehabilitation” shingle on their own.

The content taught at each institution is “pretty much the same,” Dr. Blake says. “You need to know your anatomy” and how to properly give a dog physical therapy depending on the diagnosis. Each course lasts a couple of weeks, after which the student must pass a test.

Another more extensive training for veterinarians alone is to become board-certified in veterinary sports medicine and rehabilitation. This requires completing a residency that typically lasts at least two years, taking a number of courses, and sitting for a rigorous qualifying exam.

But seeing such a doctor for rehab is usually reserved for canine athletes and working dogs who “have a job outside of just being a family pet,” Dr. Blake says. These are dogs who need to get back to a high level of function, if you have a police dog, for instance.

“I’m not saying a vet certified in rehab can’t handle these dogs,” Dr. Blake says, “but when you’re boarded, you have more training, are better equipped to make diagnoses.”

Vets with board certification are not always the ones who do the physical therapy with their patients. “Many boarded people work with someone certified in rehab,” Dr. Blake says, just like an orthopedist or other physician for people might prescribe rehab but then send the patient to a physical therapist to see it through. For both animals and people, the doctor makes an appropriate diagnosis, which sets the stage for the right exercises. Veterinary neurologists send dogs to people with certification in canine rehab, too, to help them get their strength back after a stroke or some other problem that compromises their mobility. A doctor who is boarded will also know whether rehab is the right treatment up front or whether a surgery is needed first.

Even many vets certified in canine rehab don’t do the actual exercises with their canine patients. Having the certification “gives me a better understanding of what the rehab person does,” Dr. Blake says. That way, after she performs a surgery on a dog for which the animal will need rehab to recover properly, she is better equipped to communicate with the rehab-certified person about what kinds of exercises a dog might need.

Visits to vets or technicians certified in canine rehabilitation tend to cost less than visits to the vet for other reasons, but they are not necessarily inexpensive. Ms. Lucas and Mr. Roylance pay between $70 and $80 for each weekly visit. But their certified rehab person is a vet, and the visits also include instructions for giving their dog, Brooklyn, physical therapy the other days of the week.

Just as importantly for a dog owner’s wallet, the rehab doesn’t last forever. As with people, the physical therapy with a professional goes on for a discrete period of time, and then the exercises can continue at home without weekly oversight.

Seeing the improvements in Brooklyn, Ms. Lucas and Mr. Roylance definitely feel it’s money well spent.