“His whole life I had always given him bone marrow — bones that you get in the supermarket,” says Susan Price, owner of 20-pound terrier mix Bobby. “They were larger than his jaw, but he never had trouble with them. I tended to offer them when we were having company” to keep him occupied.

Then, one day, not long after Ms. Price had people over, “all of a sudden Bob didn’t seem to be eating. He seemed listless.” A couple of days before that she had noticed that 10-year-old Bobby “kind of shuddered and seemed to be having a little difficulty swallowing. But it didn’t really register with me at the time,” she says, “although I do think that might have been the point that it might have gotten lodged in there.”

“It” was a piece of bone that had become stuck deep in his esophagus — “in a place that he couldn’t cough it up,” Ms. Price says. But it took seven to eight days for her to find that out. At first, she thought he just wasn’t eating because it was very hot weather — the dog days of August. Then her local veterinarian, not being certain what was wrong, recommended that she take Bobby from their West Hartford, Connecticut, home to Tufts.

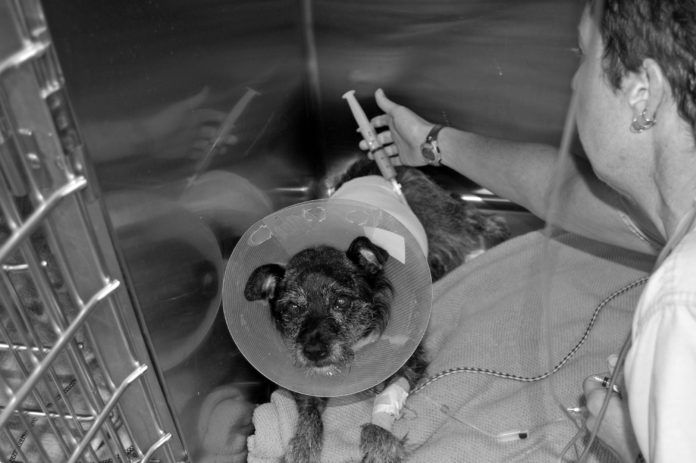

“Bobby had the worst damage to his esophagus that I have ever seen,” say his Tufts vet, Jessica Markovich, DVM, DACVIM. “I pushed the bone fragment into his stomach due to fear that pulling it out would tear his esophagus — the esophagus was already severely eroded.”

Dr. Markovich hoped the acid juices of the stomach would digest the bone, but that didn’t happen. She finally had to have the boned removed from his stomach in another procedure. In the meantime, she put Bobby on a feeding tube, as he could not swallow.

It’s an all-too-common scenario. Your dog has a stricture or obstruction in his esophagus that doesn’t allow food to travel easily from the mouth to the stomach. Or he has kidney or liver disease and has become less and less willing to eat. Or he is struggling with an oral or facial tumor that makes chewing and swallowing difficult to impossible. How can you keep him from compromising his health even further with too few calories, or from eating a diet that isn’t optimal for his medical condition?

The issue of insufficient calories becomes even more critical for a sick or injured dog than for a healthy dog. A healthy animal who’s not eating enough can at least compensate for the lack of food in the short term by turning to fat stores for calories. But a dog who is ill or injured undergoes what is known as stressed starvation, meaning that instead of using fat stores for nourishment, his body keeps using protein stores from muscle, which results in a loss of lean body mass that can make him even sicker, adversely affecting wound healing, immune function, overall strength, and ultimately, his prognosis.

Fortunately, a well-outfitted veterinary hospital can equip your dog with a feeding tube that allows food to bypass the mouth. There are two types of tubes for at-home feeding of dogs who clearly will not be able to eat enough on their own for more than three to five days and are at significantly increased risk of malnutrition. An esophagostomy tube, or E-tube for short, is placed in the esophagus, while a gastrostomy tube, or G-tube, goes directly into the stomach. A G-tube is what Bobby had.

Owners can then squirt food with a syringe into the tube, and from there it continues on its way through the gastrointestinal tract pretty much just as if it had been swallowed. “Many dogs go home with an E-tube or a G-tube,” says Tufts veterinary nutritionist Lisa Freeman, DVM, PhD, DACVN.

The Right Feeding Tube for Your Dog

It’s a little safer and easier to place an E-tube than a G-tube. “The dog has to be anesthetized,” Dr. Freeman says, “but just very briefly. And the technique for placing the tube through the dog’s neck and into the esophagus is “pretty quick and easy,” she explains. A G-tube, on the other hand, needs to be placed into the stomach either surgically or with endoscopic guidance. G-tubes are necessary when the esophagus is not working properly, say, as the result of decreased motility or if it has within it an obstruction, as in Bobby’s case.

Although both tubes can have possible complications, neither procedure is terribly risky, and owners should feel comfortable about having their dog get an E-tube or G-tube, if that’s what’s called for. The doctor will often put it in while performing another procedure that requires anesthesia so the dog doesn’t have to be anesthetized twice. Even if it’s not crystal clear that a dog will need a feeding tube upon leaving the hospital, it’s better to put one in place if it’s believed one might be needed than to find out later the dog won’t eat and have to come back.

With a G-tube, the dog will have to wear an Elizabethan collar, at least at first, so he doesn’t start tugging at or licking the tube or trying to get at the small wound created by the doctor to insert it. Bobby wore a collar, Ms. Price says, and hated it. Such collars are not necessary with E-tubes because dogs can’t reach the spot on the neck where an E-tube goes.

Whichever tube your dog ends up with, “99 percent of the time it will be commercially available food” that gets squirted in with a syringe, Dr. Freeman says. You don’t have to mix up a homemade recipe and, in fact, that can be dangerous as most homemade recipes are not nutritionally balanced or sufficiently high in calories. Your veterinarian will simply tell you which food to buy depending on your dog’s health status; sometimes it can even come from the supermarket rather than being purchased by prescription in the doctor’s office. You will most likely be instructed to blend it with a specific amount of water so that it turns into a slurry that can easily be injected. You will also be told to warm the food to body temperature before feeding. Ms. Price mixed Bobby’s food with water in her Cuisinart.

Feedings should be done slowly, usually over the course of five to 10 minutes (more if your dog is having any trouble tolerating the feedings). They tend to occur three to four times a day, and the tube should always be flushed with warm water before and after each feeding to preventing clogging. Keeping the tube capped between feedings is also important in order to keep out any debris and to further reduce the risk of clogging, which can happen if the tube dries out uncapped and then you go to put food through it later.

How difficult is all of this? Ms. Price was okay with Bobby having the hole in his stomach with the tube coming out of it. “That part didn’t freak me out,” she says. What she found unnerving was having to leave him by himself at home after the first few days, as she needed to get back to work. “I’m a single mom,” she says, “so I was really dealing with him on my own. Leaving him alone was really disturbing. I think he experienced a great deal of pain during that time but, of course, he couldn’t talk to me, couldn’t really tell me what was going on. The learning curve was really steep, I think, for both of us.”

How to Handle the Feeding Tube at Home

Along with feeding your dog through the tube, you’ll have to maintain it, keeping it clean and keeping it in place. With an E-tube, you will be instructed to put a pad around the base of it. You will also need to change the pad regularly for hygiene purposes. Further protection comes in the form of a wrap that covers the site at which the tube enters the neck. That will help if your dog tries to rub it against something. The tube, about as thick as a pen, sticks out from the body anywhere from a few inches to a foot, and keeping it covered will help stop it from catching on something and being pulled out accidentally.

The wrap will periodically need to be cleaned and checked. If it becomes wet or soiled, a visit to the vet for a new wrap will be in order. For an E-tube, you can also use a commercial cloth collar instead of the wrap.

G-tubes require a pad and bandage changings, too, along with checking to make sure the tube remains in the correct position. And whether E-tube or G-tube, Dr. Freeman says, “the tube site needs to be checked once a day to make sure there’s no redness, swelling, discharge, or other sign of possible infection. Everything should be in order. If it looks ‘funny,’ call the vet,” she advises.

Bobby gave Ms. Price a run for her money when it came to taking care of the tube. “Of course he managed to move it to a point where it wasn’t safe for him,” she comments. “He pulled a couple of sutures. You name it; he did it. I had to go to my local vet and ask them to change the bandaging around the tube because he kept playing with it. And they had to change a little part of the tube itself because he broke it off.”

Of course, it’s very important to monitor the dog’s body weight while monitoring the tube. Sometimes the amount of food must be adjusted in order to maintain weight, or increase it, if necessary. The underlying reason for the insertion of your dog’s tube also needs to be carefully monitored. Dr. Markovich checked the healing of Bobby’s esophagus many times under anesthesia to see how things were progressing.

How Long Do Dogs Need the Feeding Tube?

The length of time that a dog is fed through a tube depends on the underlying disease. “Most animals have them in anywhere from a couple of weeks to a few months,” Dr. Freeman says. “In some cases, with a special G-tube, it can be left in permanently, say, if a dog has a permanent motility problem in his esophagus. The tube itself has to be replaced once in a while because they wear out. But a dog can go through life with a G-tube, if necessary. The same is true for people. There are instances in which they’re on G-tube feedings for life.”

Don’t be upset if your veterinarian tells you your dog will remain on tube feedings from now on, say, if he has advancing kidney disease. It can be very beneficial in helping to maintain optimal nutritional status and, in many cases, improving quality of life as well as length of life.

In other cases, a dog will gradually go from being completely tube-fed to eating more and more food by mouth and less by tube until the tube can finally be removed. Dog owners should note, however, that a G-tube must be left in for at least 10 to 14 days, even if your dog starts eating enough on his own before that. The reason is that a tight wound called a fistula has to heal and create a snug junction between the stomach and the body wall, and it takes on the order of a week and a half to two weeks (or more, if the dog has poor wound healing) for that to happen. If the tube comes out ahead of time, food leaks from the stomach into the abdomen — an emergency situation.

Bobby had his tube in for about a month, after which Ms. Price switched him from the dry food she had fed him since he was three months old to canned food. She has never taken him off the soft food because, she says, “I don’t want to tamper with success, although “he’ll still eat crackers and other jagged things” sometimes. But “I don’t give him the bones anymore,” she says with a laugh.

The ordeal is now almost two years behind her and Bobby, and the now 12-year-old dog is “phenomenal,” Ms. Price says, although it was touch and go for the longest time. Dr. Markovich remarks that once Bobby’s esophagus started to heal, she no longer worried that it would perforate but then had to be concerned that it would “scar or stricture, causing a narrowing that we would have had to try to dilate with balloons.” But, she says, “he healed remarkably well, with no tears or strictures.”

Ms. Price says that “he is spirited and energetic, the same dog he always was. [We could hear him enthusiastically barking for attention as we interviewed Ms. Price by phone.] I even forget about the emergency sometimes,” she says. “You would never know that he went through that. For the longest time he had a patch where they shaved him to put in the tube, and the hair hadn’t grown back. But even that’s not noticeable anymore.”