Your dog is not herself. She’s tired more than usual, perhaps kind of weak and mopey, and has lost much of her appetite. Does she have an infection? Might she be anemic? Could it be something more serious?

Maybe she’s simply about to undergo an operation and the vet wants to check her overall state to see if the standard dose of anesthesia will need to be adjusted. Or her health is perfectly fine but she’s getting on in years, and her doctor wants to get a baseline of her general health at age 8, or perhaps 10.

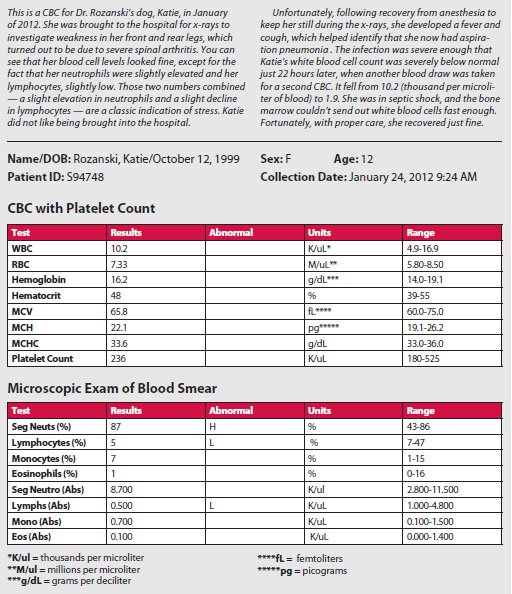

For any and all of these reasons, veterinarians order a complete blood count, commonly referred to as a CBC. “It’s a very common, everyday lab test,” says Your Dog editor-in-chief John Berg, DVM. “We probably run 50 CBCs a day here at Tufts.” A general screening test, it sometimes yields direct answers about a dog’s condition, and sometimes gives clues about what other tests need to be ordered to get to the bottom of an illness.

A CBC, which costs in the neighborhood of $50, looks at two things: 1) the numbers of different types of cells in the blood and 2) what those cells look like. The numbers are tallied by a machine. A laboratory medical technologist injects a dog’s blood into it, and it literally does all the counting, after which it spits out the results.

As for what the cells look like, a veterinarian board certified in clinical pathology or perhaps a highly trained lab technician looks at a blood smear under a microscope. At Tufts, a technologist will look first and then flag anything “funny” for the clinical pathologist to examine. This is often true at other labs as well. The person will be able to tell the different kinds of blood cells apart from each other and also, differentiate normal-looking cells from those that are abnormal looking.

When you look at a CBC printout, the count comes at the top, above cell appearance, so that’s what we’ll discuss first here.

Blood Cell Counts

There are three types of blood cells: white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets.

White blood cells help the body fight infections. Thus, if white blood cell levels are high, it can very well be an indication of an infection. “A bacterial infection is the most common kind that we see with high white blood cells,” says Dr. Berg, so the suspicion would be that the dog needs an antibiotic to tackle the offending bacterial problem. But for what? That’s where further testing might come in. If the dog is coughing, perhaps a chest x-ray could pinpoint pneumonia in the lungs, which would prompt a veterinarian to obtain a culture from the airway.

A white blood cell count that’s super-high often indicates leukemia — cancer of the bone marrow. The bone marrow produces all blood cells, not just white ones but also red ones and platelets. But the malignancy causes the marrow to produce too many of the white variety. A normal white blood cell count is more or less in the range of 5,000 to 17,000 (per microliter of blood), whereas an infection might cause an increase to something along the lines of 25,000, and leukemia, to 100,000 or more.

Note that sometimes white blood cell counts are elevated, and it has nothing to do with illness. It’s the result of the dog’s stress from having to come to the doctor’s office. Consider that a certain type of white blood cell increases in count in response to the release of cortisol — a stress hormone that might become elevated as the result of a dog’s having to come into the hospital with a lot of other scared dogs, or even just the stress of not feeling well. A stressed dog who’s not otherwise sick may have a white blood cell count that “looks like” an infection is present when it is not.

Sometimes a dog’s white blood cell count turns out low rather than normal or high. In those cases, says Elizabeth Rozanski, DVM, a Tufts veterinarian board certified in emergency medicine and critical care, you’ve got to ask yourself, “Is the bone marrow not making enough white blood cells? Is there an overwhelming infection that’s using more white blood cells than the bone marrow can create?” In many cases, Dr. Rozanski says, a low white blood cell count results from chemotherapy, sepsis (overwhelming infection), or parvovirus. The virus destroys all rapidly dividing cells, including those in the bone marrow and cells lining the gastrointestinal tract.

Red blood cells, by far the most numerous cells in the blood and the ones that make it look red, are the cells that carry oxygen to all the tissues in the body. There are three ways in which they’re counted.

RBC, which stands for “red blood cells” (see second line on chart above), is an overall count. Hemoglobin (see third line) is the oxygen-carrying molecule of a red blood cell. “It just sort of tags along with RBC,” Dr. Berg says. If one is low, the other will be low, and vice versa. Hematocrit is the percentage of the volume of the blood that is comprised of red blood cells — another way to get at the amount. When veterinarians talk about anemia — low red blood cell count — it is generally the hematocrit level they are referring to.

Diagnosing anemia doesn’t get at the root of the problem. The doctor needs to find out why the red blood cell count is low. It could be loss of red blood cells due to internal bleeding within or around a particular organ, or it could be external loss due to injury or intestinal bleeding. It can also be a failure to produce enough red blood cells, which is sometimes an indication of abnormalities within the bone marrow, such as leukemia or infection. (Kidney disease may also cause a mild non-regenerative anemia that doesn’t allow enough red blood cells to be produced.) Finally, it can be destruction of red blood cells. Red cell destruction may result from an overzealous immune system, which is termed immune mediated hemolytic anemia; or from toxins such as zinc; tickborne diseases; or even cancers.

In some cases, the red blood cell count may be higher than normal. This is termed polycythemia and may be “relative” or “absolute.” Relative is by far the most common. It means that the red cell count appears high because the patient is dehydrated, typically from severe vomiting and diarrhea. Absolute means the number of red blood cells is actually higher than it should be. That may occur in association with rare forms of heart disease that allow the blood to bypass the lungs without getting oxygenated, or it may develop due to tumors of the bone marrow or kidney.

Along with assessing the level of red cells in the blood by looking at count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit, the machine that spits out the numbers also tells a few other things about red blood cells that help veterinarians diagnose disease.

One is MCV, or mean corpuscular volume, which actually measures red blood cell size. When red blood cells are first released from the bone marrow, they are relatively huge and contain a nucleus. These immature red blood cells are called reticulocytes. As they mature, they become smaller and lose their nuclei. “If a dog is anemic but we see big cells,” Dr. Berg says, “it means the bone marrow is responding to the blood loss by making a lot of new cells. We call the response regeneration, which is good. We want anemias to be regenerative. If you have a low red blood cell count with a low MCV, on the other hand, that might be a problem. It could mean there’s an issue that’s not letting the bone marrow respond to a loss of blood, either internally or externally. The bone marrow is “tired,” and it needs to be found out why. Maybe there’s chronic iron-deficiency anemia or chronic internal bleeding, like a slow leak, that needs to be identified and stemmed.

MCH stands for mean corpuscular hemoglobin, or the average amount of hemoglobin per red blood cell, while MCHC signifies the closely related mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration. These numbers, too, Dr. Berg says, can help the doctor begin to sort out the cause of anemia as well as the ability of the bone marrow to respond.

Platelets, the third type of blood cell, are those involved in clotting. Their job is to plug little defects in the linings of blood vessels. “The dog hits her paw against something or gets bitten — the platelets are the first line of defense,” says Dr. Rozanski. After the platelets plug the initial leak, clotting factors help provide a more permanent seal until repair occurs.

If the platelet count is low, a condition termed thrombocytopenia, or if the platelets don’t work well — thrombocytopathia — unexplained bleeding may occur. This bleeding is usually under the skin (think of bruises), but animals may also experience gastrointestinal bleeding or nasal bleeding. Sometimes, small little red dots are seen on the skin (termed petechiae). These arelittle bleeds.

Low platelet counts are commonly caused by immune destruction of the platelets; in this case, the body’s immune system accidently decides that the platelets are “invaders” and kills them off in circulation. This can generally be treated effectively. Other causes for low platelets include severe blood loss, infection (by ticks), and cancers. Cases where the platelet count is adequate but the platelet function is abnormal may be caused by drugs, such as aspirin therapy, but also may result from some infections, kidney failure, or cancers.

Very rarely does platelet count go up — a condition called thrombocytosis — but certain diseases or situations can cause it to happen. These include chronic steroid therapy, Cushing’s disease, or prior removal of the spleen.

The Blood Smear for Dogs

The smear of blood that a veterinary clinical pathologist examines under a microscope is pretty much all about the different types of white blood cells — of which there are four main kinds. In the lab report, they are typically expressed both as a percentage of the total white blood cell count and also in absolute numbers (indicated by the term “Abs” in parenthesis).

First come the neutrophils, which are the most common white blood cells in dogs, accounting for 70 to 80 percent of them. On the CBC results, under “Microsopic Exam of Blood Smear,” you’ll see a line for seg neuts, meaning segmented neutrophils, and sometimes one for band neuts, which stands for band neutrophils. Segmented neutrophils are normal, mature neutrophils. On the slide, their nuclei are elongated and pinched in several locations. Band neutrophils, shaped sort of like a banana, are immature ones that have not yet undergone segmentation. It’s when there’s a serious bacterial infection that the clinical pathologist might see band neutrophils. The bone marrow starts releasing the neutrophils before they’re mature in an effort to tackle the bacteria causing the problem.

Lymphocytes appear next on the lab results. They are the second most common type of white blood cell, accounting for close to 20 percent of them. Interestingly, while stress can raise white blood cell count in general (neutrophils specifically), it can lower lymphocyte numbers. A dog with mildly low lymphoyctes might not be sick but simply feeling stressed from the trip to the hospital.

The monocyte count isn’t particularly telling on its own, but like the neutrophil count, it can go up in the case of infection. A high eosinophil count, on the other hand, can indicate an allergic reaction, as well as the presence of disease caused by parasites, such as intestinal worms or heartworm infection.

“If the parasite is a blood cell parasite, you may actually see the parasites on the slide,” says Dr. Rozanski. “Here in the northeast, a tickborne disease called Anaplasma is one of the more common ones we see. When it’s detected, the veterinarian then knows that’s what she has to treat.

Always Exceptions to Blood Count Numbers

While a CBC will give the veterinarian numbers and let him know whether they fall within the normal range or outside of it, not every number that falls out of range means there’s a problem. For instance, greyhounds tend to have higher red blood cell counts than other breeds, says Dr. Rozanski. “Other sight hounds do, too, she says, but greyhounds specifically.” All those extra richly oxygenated red blood cells no doubt help them in running.

Some dogs may also tend to run just a little low or a little high in blood cell counts compared to what the lab calls normal. That’s why it’s good to get a baseline as your dog transitions from middle age to geriatric at around age 8 or so.

Then, too, there’s an art to interpreting the numbers, as there can be false negatives and false positives. For instance, a dog can be suspected of having pneumonia — she’s coughing and running a fever — but the white blood cell count may be normal. It could be that the symptoms are running ahead of the bone marrow’s response, and the vet may decide to prescribe antibiotics even though the white blood cell count is in the normal range. He goes with his hunch that the blood cell count is showing a false negative. That is, the numbers are right; they’re just not telling the whole story.

“It’s one of the reasons some tests are run multiple times,” Dr. Berg says. “An individual test at a particular moment in time may fail to capture the problem.”

Certainly, says Dr. Rozanski, “we don’t worry if one of the values is a tenth of a point off normal. Often, animals are a hair outside the normal range without that meaning anything, just like in people.”

Dr. Rozanski advises keeping a folder of your dog’s CBC test results. “It becomes especially important if you don’t go to the same vet the entire length of your dog’s life,” she says, “or if you’re a snowbird,” spending summers up north and winters in Florida and therefore have two different vets. “It’s really helpful, particularly in an emergency,” she counsels. “If a dog has had the same subtle abnormality for years that hasn’t caused any harm, the vet will know he doesn’t need to chase it down to find out what’s wrong. On the other hand, knowing your dog’s baseline will help the vet determine if something has changed that needs investigating.”

PCVs for Dogs

Sometimes an entire CBC is not needed to assess a dog’s red blood cell status. There are cases in which a veterinarian will order just a PCV, which stands for a test of packed blood volume. It’s a simple point-of-care test rather than one that requires blood be sent to a lab. A little blood is taken from a dog at her “bedside,” then spun in a centrifuge, which separates out the different types of cells. “From there we just literally look at the blood inside the tube,” Dr. Berg says, “measuring the proportion of the column of blood that’s red. It’s a very quick indication of what the patient’s red blood cells are doing. It’s a low-tech version of the hematocrit.”

This is the first in a series of articles on basic lab tests. Next month: the chemistry profile.