BIGSTOCK

The pain is not mild to moderate; it’s severe, to the point that the dog may not be able to eat. In fact, she may yelp even when you just touch her back and might possibly be unable to move or stand. The suffering and paralysis can come on either with a past history of back pain or with absolutely no prior warning.

Moreover, the pain doesn’t wax and wane, as it does with arthritis. Your pet may have real reluctance not only to jump or use the stairs but even to walk. And she may be unusually quiet, sometimes to the point of hiding — or, conversely, unusually aggressive or irritable. Get her to the doctor.

There’s a good chance a disk in her back is pressing on her spinal cord, or on a nerve root somewhere in the long column of bones, also known as vertebrae, that make up her spinal column. That is, she may very likely be suffering from intervertebral disk disease.

COURTESY BUSH VETERINARY NEUROLOGICAL SERVICES

The anatomy of an illness

“Imagine taking a piece of Playdough and rolling it out into a long thin tube,” says Bill Bush, VMD, DACVIM, a veterinary neurologist who owns the largest veterinary practice in the world, with offices in Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia. “That’s the spinal cord, which has a lot of nerve roots. It’s inside a bony box — that is, protected by all the vertebrae that make up the spine. And “it’s pretty tight in there” without much wiggle room.

Cushioning the vertebral bones, coming between them (“inter”) are disks. They operate much like joints next to bones in other parts of the body, acting as shock absorbers and thus keeping movements from jarring the bones in the back and shielding from pain. But sometimes a disk can bulge, pushing right into the spinal cord. (When this happens to people, it’s most often in the lower back.) That can cause stretching of the nerves there, causing horrific pain and not allowing messages to go from the brain through the spinal cord to the limbs signaling movement, which is why some dogs with intervertebral disk disease become paralyzed, and unable to move their hind legs.

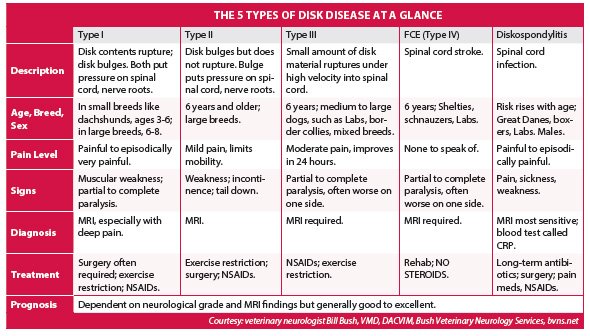

Sometimes, a disk doesn’t only bulge but also ruptures. The contents of the disk dehydrate, becoming mineralized — think of the jelly inside of a jelly donut becoming sandy, Dr. Bush says — and break through the disk, striking and persistently compressing the spinal cord. The compression causes great pain and, if the right nerves are hit, can make it difficult for a dog to control urination or defecation. It can happen all of a sudden. Your dog seems absolutely fine one moment and is in debilitating pain the next. That’s the Type I version of disk disease in dogs. One in three dogs who ends up with disk disease gets this kind.

It’s very common in dachshunds (affecting about one in six of them) and other small breeds that include shi tzus, Lhasa apsos, miniature poodles, beagles, and cocker spaniels. “Those are the breeds that come to mind with type I,” Dr. Bush says, although Type I can occur in larger breeds as well — Dalmatians, German shepherds, Rottweilers. But larger dogs tend to be middle aged when it happens, whereas the small dogs are generally on the younger side. When afflicted, the pain can be so great they won’t let you pick them up. Mixed breeds can get Type I, too.

With Type II, there’s no extrusion of disk contents, only the bulging of the disk. About half of all dogs who get disk disease get this kind. It occurs typically in larger dogs. “Dobermans in the neck and German shepherds in the low back — those are classic breeds for those locations,” Dr. Bush says.

“While Type II is the most common,” he adds, “it’s probably not recognized as frequently as it should be.” The pain may not be as dramatic as with Type I, so the signs are often confused with arthritis. But the dog may be unusually weak or incontinent and keeping her tail down.

Also, with Type I, if a dog is in severe pain and very weak, the veterinarian can “flip over the paw, and if the paw doesn’t correct itself, it means the signals aren’t passing quickly enough through the spinal cord. That alerts the vet right away,” Dr. Bush comments. There’s no clinical exam quite like that for Type II.

“The level of discomfort in Type II patients is often under-recognized,” he says. “It’s more than what we once knew, and people can be inadvertently under-sensitive to the pain their dogs are in. If your dog seems to have arthritis but is not eating” and really having a hard time, with the discomfort as more of a constant rather than intermittently, Type II disk disease should be explored as a cause of the malaise.

There are three other types of intervertebral disk disease in dogs, too. Type III is known scientifically as low-volume, high-velocity disk extrusion. The low volume refers to the fact that the disk ruptures, as with Type I disease, but only a very small amount of the inner contents come out. But the disk ruptures at a very high velocity, “with the contents like a very small bullet being shot at a very high speed,” Dr. Bush says. “This can cause bleeding and pain and damage to the spinal cord, and the contents can even enter the spinal cord,” he reports. It makes up about 10 percent of disk disease and occurs in middle-aged large breed dogs like Labs and border collies.

The signs of the fourth type of intervertebral disk disease — fibrocartilaginous embolism, or FCE — overlap with those of Type III disease and include not just pain but also partial loss of voluntary movement, or even complete paralysis. But its mechanism is different. A piece of disk material enters the blood supply and causes a stroke to the spinal cord. Specifically, blood flow to the spinal cord is obstructed, resulting in tissue death there. Comprising less than 5 percent of cases of disk disease, FCE affects the same dog breeds as Type III does.

Finally, there’s the fifth type — diskospondylitis. Affecting only 1 percent of dogs with disk disease, it’s a disk infection that causes the pain and weakness, generally in larger male dogs like Great Danes, boxers, and Labs. The risk increases with age.

Making the correct diagnosis

For a diagnosis to confirm any type of disk disease, there are “three things that I would use,” says Dr. Bush: “MRI, MRI, and MRI.” Magnetic resonance imaging does not come cheap, he acknowledges. For instance, he says, “$1,400 is the least expensive I’ve heard of on the east coast, with $2,200 being the most expensive.” But, he says, “if there’s any way a client can swing it if their dog has back pain or weakness,” that’s the way to go. “With Type I disk disease,” he comments, “a CT scan is a good substitute. But MRI is the only imaging modality that directly images soft tissue,” such as the tissue in a disk. “With a CT scan or x-ray, you’re looking at the difference in how rays pass through tissue. MRI gives a direct image,” he points out. “It’s also good at showing subtle changes in water density” when a disk ruptures. “So you can diagnose with a high level of accuracy.”

Of course, the veterinarian also has to perform a clinical exam, touching the dog and observing her. And x-rays and CT scans may very well need to be ordered. But confirmation of a diagnosis of intervertebral disk disease — and which type — has to be accomplished with MRI.

Treatment options include surgery, medicine, and rehab, or physical therapy

With Type I disk disease, says Dr. Bush, “it’s thought to be a surgical problem because you have a big piece of disk material that’s way out of position, putting a lot of pressure on the spinal cord and causing weakness to paralysis, typically. A recent study says that as many as 17 percent of dogs with Type I who don’t get help end up dying because the spinal cord softens and dies. Surgically removing the disk and restoring blood flow and eliminating pain is thought by most to be the way to go. It’s strongly preferred.

“Among dogs who get surgery for Type I disease, the success rate is about 95 percent. Of course, we’ve also gotten very good at sorting out which dogs will benefit from surgery with MRI. That helps the numbers.”

MRI followed by spinal surgery is expensive — anywhere from roughly $5,000 to $6,500. It’s a situation where already having health insurance in place for your dog really pays off.

Surgery is also a very good option for dogs with Type II disk disease. “Success rates aren’t quite as high — maybe 85 percent,” Dr. Bush says. “But it’s still often recommended.

“Type II patients who aren’t going to get managed surgically will get managed medically,” he remarks, “although medicine is also used as an adjunct to surgery. The medicines we tend to use are anti-inflammatories in the form of non-steroidal drugs, or NSAIDs. We no longer use steroids for pain control — too many side effects. In certain studies, steroids have been shown to reduce quality of life scores and also to increase chances of recurrence because they can cause loss of muscle and weakness of the ligaments that surround the spinal column.

“In addition to anti-inflammatories, we prescribe gabapentin. It’s a very effective drug for nerve pain in animals,” Dr. Bush remarks. “In fact, we put every dog with nerve pain or suspected nerve pain on that medicine. We want to inhibit pain signals from getting up to the brain.” Dr. Bush also notes that tramadol is used to control pain and adds, “I do think there’s a nice role for acupuncture in treating pain.”

Type III disk disease — the kind in which it’s as if a piece of the disk acts like a bullet shooting into the spinal cord — can’t be relieved with surgery since it’s not a matter of pressure on the spinal cord or nerve root. The fourth type — FCE — in which the spinal cord suffers a stroke, does not have a surgical solution, either. For both of those, the remedy is pain medication and rehab, or physical therapy.

Physical therapy also plays an important role in dogs with Type I or Type II disk disease who undergo surgery. Dr. Bush stresses that the therapy must be progressive, that is, very gradual. “Dogs with Type I, II, or III need time to heal,” he says. “We try to keep all four feet on the ground at all times for about six weeks. This means cage confinement with just being walked a few steps outside for the dog to relieve herself. No climbing stairs, no moving around in general.” FCE doesn’t require cage confinement, but it does necessitate gradually more challenging rehab.

For infection, a fifth cause of disk disease formally called diskospondylitis, the effective antidote is antibiotics, often combined with surgery, especially if there’s weakness, Dr. Bush says. “The mortality rate with infection is 30 to 50 percent,” he says. “But when you perform surgery you improve delivery of antibiotics to the spine, and the patient tends to do better. At least, I think that’s the reason.”

Going forward after treatment

As dire as disk disease of any type can be, the good news is that with appropriate treatment, most dogs make complete or nearly complete recovery to their previous level of functioning. Make no mistake. Even after surgery for Type I or Type II disease, there’s a recurrence rate of about one in five, Dr. Bush says — a low risk but not exceedingly low, and owners need to be aware of that.

But for the 80 percent of dogs who do not experience a recurrence, the quality of life goes back to what it was before, or nearly to what it was. “The exception is dogs who are paralyzed to the point that they can’t urinate or defecate at will,” Dr. Bush says. “Probably even with surgery only about half of those dogs make a really functional recovery” because part of the spinal cord will have essentially died. Fortunately, he adds, “MRI can predict who’s going to get better even when they have lost feeling in their back legs.” It gives owners more of a sense of whether going through the surgery is going to be worth it. If death of the spinal cord is seen on the MRI, Dr. Bush remarks, a veterinary neurologist would support the decision for an owner to choose euthanasia.

For dogs with Type II disk disease who do not undergo surgery but instead are managed medically, they are typically on drugs for the rest of their lives, “and they do okay,” Dr. Bush says. “You don’t eliminate the clinical signs of disease, but you control them,” make them more manageable.

Dogs who have Type III disease or FCE fare well, too. With proper medical management and rehab, two thirds of those with Type III return to walking across all grades of the illness. Those whose illness is not too severe to begin with have an even higher success rate. For dogs with FCE, about 75 percent improve to functional status with proper medical and physical therapy.

Dogs with infection are often on antibiotics for an entire year and often come out okay. Surgery can improve the outcome for dogs with infections of the spine, with a majority of those dogs doing well.

People should recognize that to some degree the outcome is dependent on how soon you get your dog to the doctor. With Type II disease, for instance, which doesn’t come on as suddenly and dramatically as Type I, if you wait until the dog is incontinent, or miss a proper diagnosis because you assume the lack of mobility is the result of arthritis, “nerves going to the sphincters that control urination and defecation will have degenerated,” Dr. Bush says. “At that point, they will not come back with decompressive surgery.”