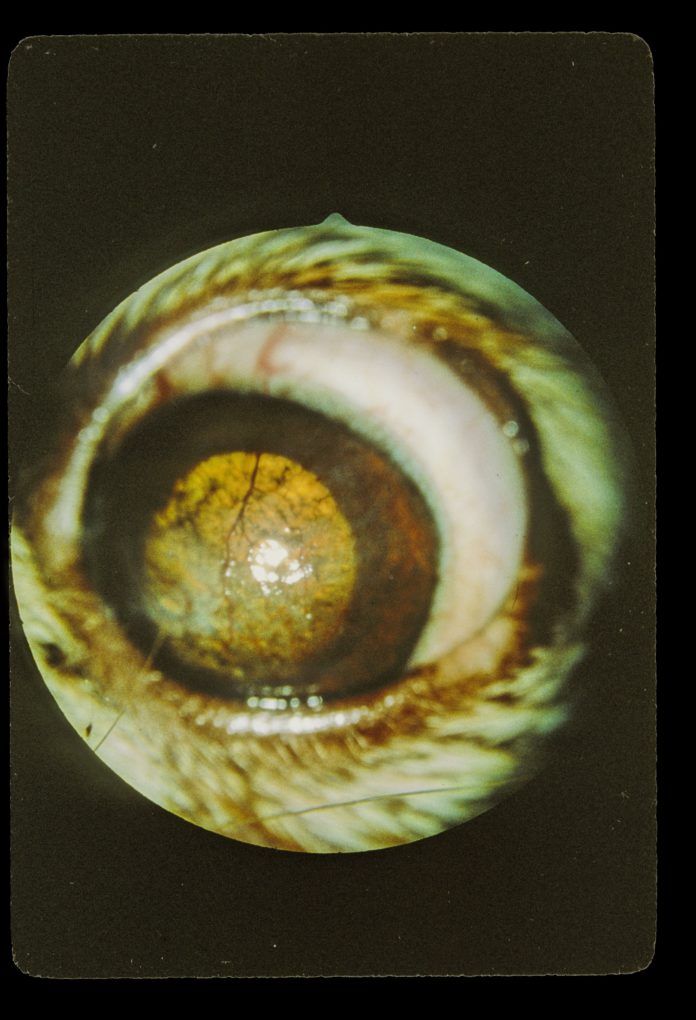

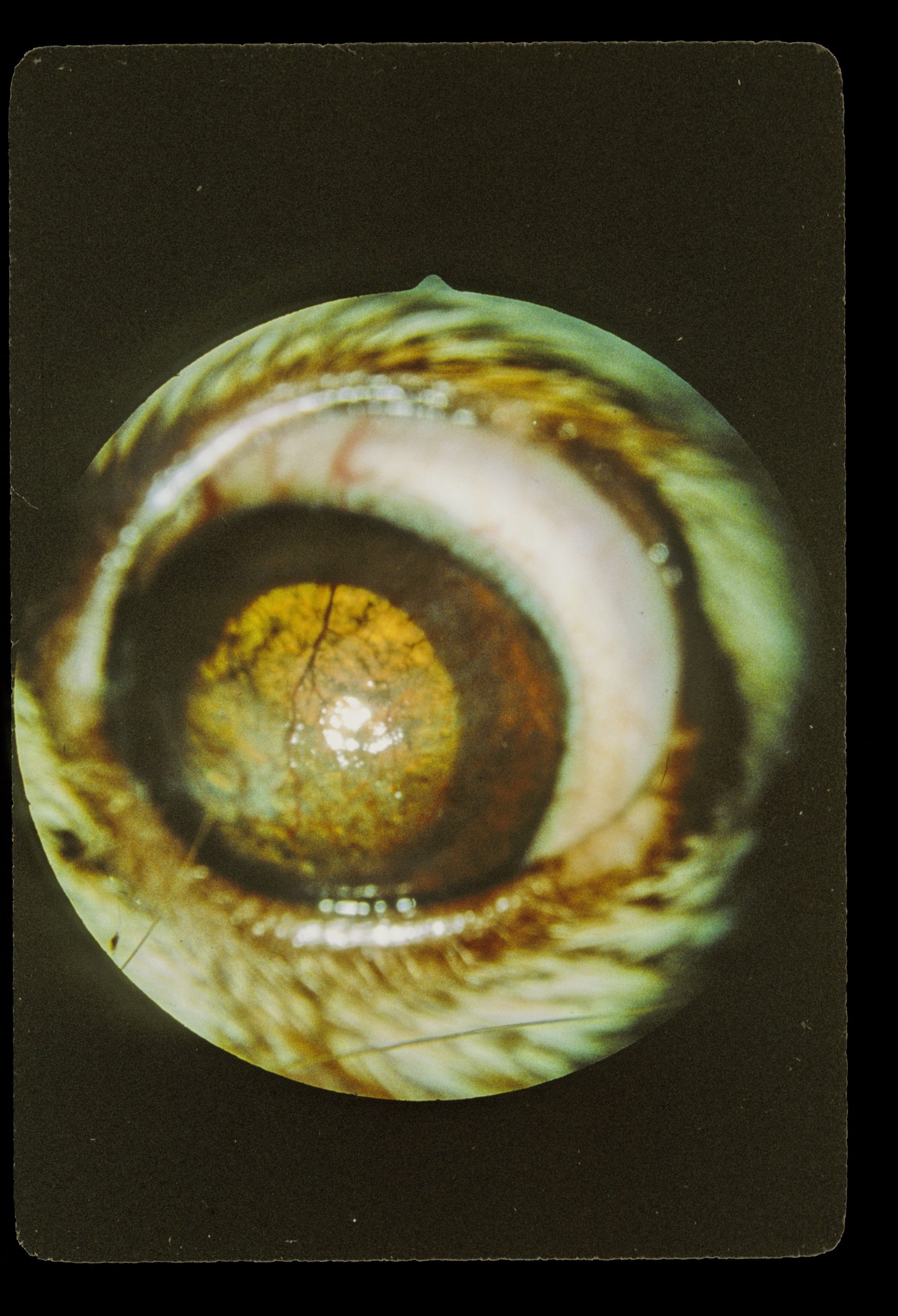

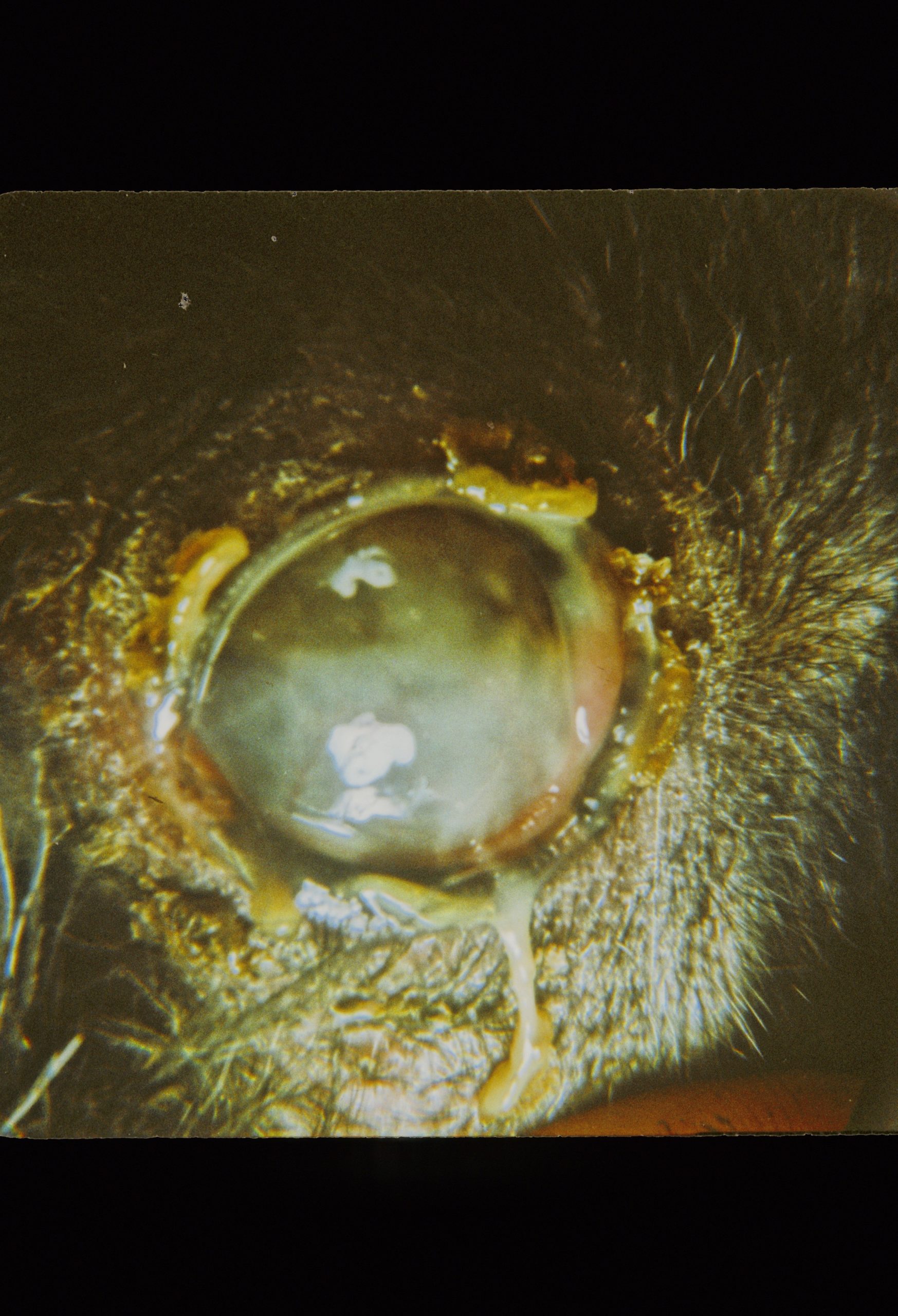

Gloria Mooney is worried. Her dog, Sparky, all of a sudden began to have trouble opening his eyes. It was not completely out of the blue. Weeks earlier, he had what she calls a skin breakout, with ulcers (open sores) appearing all over his body, including inside his mouth, his nostrils, eyes, and so on. Those areas were breaking and failing to heal. Sparky’s veterinarian assumed some kind of allergy was responsible for the problem and prescribed steroids and other medications, which cleared up the open wounds everywhere but in the corneas of Sparky’s eyes. The cornea is the clear outer surface of the eye, and problems there are serious. The cornea accounts for more than two thirds of the eye’s optical power.

The dog was then referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist, who found a large ulcer on one cornea and a small ulcer on the other. Apparently, the smaller ulcer was healing, but the larger one was deep enough that the doctor recommended corneal graft surgery, in which healthy tissue is sutured into place on the cornea to replace the damaged tissue of the ulcer.

But now Sparky has a new problem — or perhaps a newly discovered problem: dry eye. He is not responding to any medications, and the ophthalmologist is talking about performing an additional surgery to re-route moisture from one of Sparky’s salivary glands into his bad eye. If the eye remains dry, Sparky will lose his vision. Ms. Mooney wants to know if she should go ahead with the second surgery, as she has heard it has downsides.

Tears and their function

Like people, dogs produce tears that comprise what is literally considered the anatomical outer layer of the cornea. This outer layer, or film, provides lubrication for the cornea’s surface, but it also does much more. It helps nourish and protect the cornea. The cornea and the lens together focus light to create an image on the retina. But if the corneal structure becomes altered because of a disease affecting the composition and distribution of the tear film, light transmission and refraction by the cornea will be affected, and vision will then be impaired.

It has to do with the fact that many of the diseases affecting the tear film take away corneal transparency, which is essential for normal vision. These diseases can lead to increased corneal thickness, an ingrowth of new blood vessels, and invasion by pigmented cells. All of these get in light’s way.

The most common reason for a compromised tear film in dogs is dry eye, which is Sparky’s problem. In medical-speak, it’s known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS). Dogs most prone to KCS include brachycephalic breeds like Pugs, Shih Tzus, and English bulldogs. American cocker spaniels and West Highland white and Boston terriers are also commonly affected because they have very prominent eyes that are more exposed to tear evaporation.

Dolichocephalic breeds, which have longer noses — think German shepherds and collies — are less prone to KCS. But any dog could end up affected. One of the most common underlying causes is an autoimmune disease, which is what seems to have led to the ulcers in Sparky’s mouth and elsewhere. Autoimmune inflammation can affect the lacrimal glands that produce tears.

In its early stages, KCS might not even be noticeable. But after a while, a dog will have some redness in the eyes, some squinting, and thick mucous discharge that can have a yellow-green color due to bacteria. If it goes on for too long, KCS becomes downright painful. Sparky is currently wearing an Elizabethan collar, in fact, because he wants to keep scratching at his uncomfortable eye, which could only serve to make the situation worse.

Treatment — Conservative at first

In its early stages, and sometimes even with more advanced cases, the first line of treatment consists of medications. And that’s what Sparky’s ophthalmologist has been trying. Past chair of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmology’s Public Relations Committee Nancy Bromberg, VMD, who practices in the DC area and volunteers her expertise at Washington’s National Zoo, also recommends that because his dry eye started with a skin issue that came on so suddenly, he undergo a complete thyroid profile because sometimes hypothyroidism can be a cause of the problem.

Ms. Mooney doesn’t say what medicines Sparky has been taking, but a common one used to stimulate tear production is tacrolimus. That’s the one Dr. Bromberg usually tries. Another is cyclosporine. It was the first drug used to treat dry eye in dogs and was so effective that it is now also used in people. Both tacrolimus and cyclosporine come as drops or ointments that need to be applied two to three times daily — for life. The frequency of treatment may decrease, depending on the response.

“I might also use dilute topical pilocarpine three times daily,” Dr. Bromberg comments, “in case the problem is due to an acute loss of nerve supply to the glands that produce tears.”

Artificial tears, that is, lubricants, are also important. “My favorite lubricant is Optixcare with Hyaluron,” Dr. Bromberg says. It is a high-viscosity product that stays on the eye longer than other formulations. That’s helpful because it means that a dog owner can apply the drops less frequently than preparations that don’t remain on the ocular surface for as long; some owners find it difficult to apply the drops frequently, which could lead to a lack of owner compliance — and the dog remaining uncomfortable and losing more vision.

Of course, if an autoimmune component is present, as it seems to be in Sparky’s case, immune suppressants could actually help to correct the underlying problem.

When conservative treatment fails

“If I exhaust all medications and diagnostic possibilities and nothing has helped,” Dr. Bromberg says, “I will consider recommending surgery.” The type of surgery she will consider is the kind Ms. Mooney speaks of — one that will divert saliva from the mouth to the eye. It’s called parotid duct transposition, or PDT. That means a duct from the parotid salivary gland is redirected so that it opens between the third eyelid and the lower eyelid. Normally, the opening is above one of the upper molars, delivering saliva to the oral cavity. After the surgery, each time the dog salivates, saliva goes into the eye and serves as replacement lubricant for the tears that are not being produced. Because there are several salivary glands, the loss of the parotid gland’s saliva in the mouth does not affect eating or digestion.

“The operation is usually successful,” Dr. Bromberg notes, “but has its own issues. “Saliva is high in calcium, and it can precipitate [harden] on the cornea and cause discomfort,” she says. That side effect can be treated with a chelating agent, EDTA, that draws out the calcium deposits on the cornea. But the side effects are a hassle, which is at least part of the reason Dr. Bromberg says, “I will try medications for at least four months before I give up on them, increasing the concentration of the tacrolimus as I go.” Indeed, since the advent of tacrolimus and other new drugs, surgery has become less common. The medical therapy is that good.

Moreover, there’s usually plenty of time to get a dog over the problem since it tends to develop slowly. Of course, that has not been the case with Sparky, which may be why his ophthalmologist is recommending the surgery at this earlier stage. Time may not be on his side as far as saving his vision and decreasing his discomfort, which can progress to outright pain.

We cannot diagnose or recommend treatment or chart a dog’s situation from afar, so we don’t know the answer as to whether he should have the operation; we can only tell Ms. Mooney that it is sometimes used as a last resort. We hope she keeps us posted on Sparky’s progress.