You know something is wrong because your dog is just not right. She’s not eating as well as usual, isn’t as active, and appears to be suffering from an overall discomfort or malaise. What could it be?

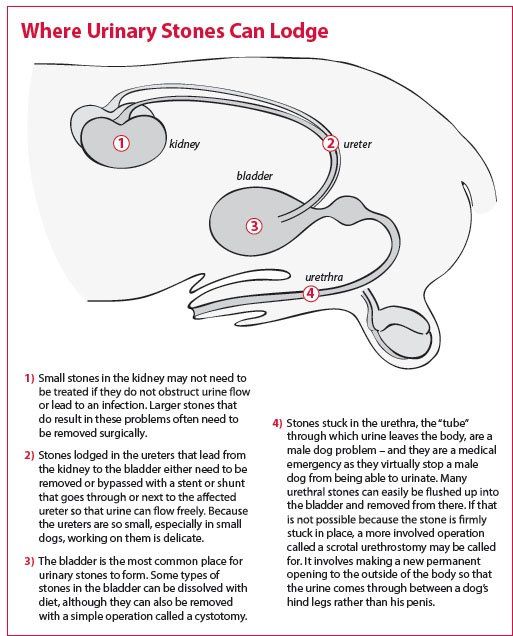

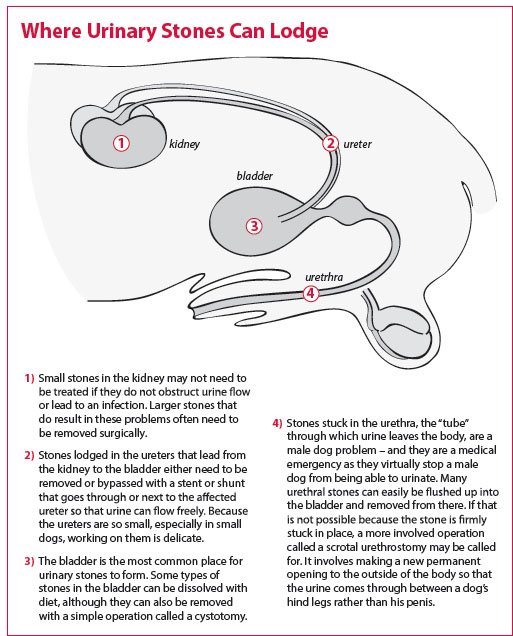

An x-ray or ultrasound reveals she has a stone, or calculus, in one of her ureters. The signs won’t be as clear as if she had a blocked urethra, which we discussed last month. That’s because a dog has only one urethra. If it becomes blocked with a urinary stone, your pet won’t be able to urinate at all, or only very little. It’s a true medical emergency because not being able to void urine means the toxins it carries out of the body end up in the bloodstream instead, making the animal very sick.

A blocked ureter generally isn’t as dire because each dog (like each person) has two, one coming from each kidney into the bladder, where urine is stored. There’s only one urethra, on the other hand. It’s the “tube” from which urine leaves the body. Granted, in rare instances both ureters may be blocked with stones, but in most cases, it’s just one. But the stone still needs to be dealt with — it’s what’s making the dog feel sick and uncomfortable, after all. The problem: it’s not that easy to treat.

“The fundamental challenge with stones obstructing a ureter is that the ureters are very small,” says Tufts veterinary surgeon John Berg, DVM, “tiny little tubes. And the smaller the dog, the smaller the ureters, to the point that in a little dog, there’re literally no more than three to five millimeters in diameter” — as narrow as one ninth of an inch!

Beth Mellor

In most cases of ureteral stones, an initial attempt will be made to dislodge the stone by administration of intravenous fluids, prior to considering surgery or other more invasive measures. Fluid administration increases urine production, which may cause the stone to be flushed into the bladder, where it can be removed with a fairly simple surgery called a cystotomy.

However, if fluid administration doesn’t do the trick, there are three additional ways to get at the problem.

Surgically removing the stone from the ureter. “Our first choice is often to make an incision in the ureter, take out the calculi, and then suture it up,” says Dr. Berg. Unfortunately, he comments, “the ureter can be so small it’s difficult to see with the naked eye and then suture it, especially if it’s a small dog.

“If the surgery suite has an operating microscope, which we have at Tufts [but which are absent from most veterinary centers], that magnifies everything, which makes it easier.” But even so, Dr. Berg says, an incision in a ureter is slightly prone to stricturing when it heals. That is, excessive scar tissue may form, so that the scar tissue itself begins to obstruct the flow of urine. Or the incision in the ureter may leak — into the abdomen. And urine leaking into the abdomen causes severe problems. A dog can become very sick and have to have another surgery — or even have the kidney removed if the ureter can’t be re-sutured adequately.

“So while taking stones out through the ureters can be done — and we certainly do it — it’s not easy,” Dr. Berg says. “We tend to reserve it for dogs that are about 45 pounds or larger and have wider ureters. But two other methods have been developed.”

Inserting a stent. A surgeon can place a stent, or tube, in the ureter that goes its full length, “from the kidney clear down into the bladder,” says Dr. Berg. “The urine is then carried through the tube.” That doesn’t dislodge the stone. It stays stuck right where it is (although it may eventually loosen and pass on its own). But the dog is no longer uncomfortable. “The source of pain when there’s a stone is that the urine can’t flow,” explains Dr. Berg. “The stone causes the ureter and kidney to become dilated, or stretched out, from the pressure of the urine that cannot flow past the stone, and it’s the stretching that hurts, not the stone itself. So if you can get the urine to flow through, the pain goes away.

“A stent is not that easy to put in either,” Dr. Berg notes, “but it’s less complication-prone than making an incision in the ureter.” Scarring of the tissue is not an issue, nor is leaking of the urine into the abdomen.

Inserting a ureteral bypass catheter. Instead of inserting a stent into the ureter, a surgeon also has the option of bypassing the ureter altogether with a catheter. Running from the kidney through subcutaneous fat just under the skin, then back through the body wall and into the bladder, it allows urine to circumvent the ureter completely. “The advantage here,” says Dr. Berg, “is that a catheter outside the ureter is easier to place than a stent that goes down the ureter itself.” The catheters are a recent development designed to alleviate the technical difficulties inherent in placing stents. Because of their ease of placement, they may eventually become the first choice for treatment of stones that cannot be dislodged with fluid administration.

Both a stent inside the ureter and a catheter that circumvents it are “well tolerated over the long term,” says Dr. Berg, with “low complication rates. But most veterinary offices don’t perform the procedures to place them; they tend to be only through referral. And not every referral center will offer them. Even the surgery in which the ureter is opened is not widely available.” It‘s mostly at veterinary schools and a few private practices. Thus, it may take some shopping to find the veterinary practice closest to you that offers these solutions.