Poor little Scottish terrier Newt was barley two months old and had been in his new home only a few weeks when, according to his owner, Jackie Strom, “he kind of rolled over on his back, his arms and legs going. His eyes were sort of in the back of his head, and he lost control of his bowels. It probably didn’t last much more than a minute or so.”

Ms. Strom, who lives about 40 miles east of Atlanta, took Newt to the veterinarian, who warned her that Newt was never going to have a normal life. A week and a half to two weeks later, when it happened again, she took him to an emergency room vet, who prescribed the anti-seizure medication phenobarbital. It didn’t help. “I came home from work one evening,” she relates, “and he was just trying to be in the corner by the refrigerator. He really didn’t move, and his face was all wet from drooling, so I knew that something must have happened. I figured he must have had more than one in a row. I took him back to the emergency room vet, where he spent the night, and then they referred me to Dr. Neary.”

Enter the specialist

Casey Neary, DVM, DACVIM, is a board-certified veterinary neurologist at Bush Veterinary Neurology Service, the largest veterinary neurology practice in the world, with offices in several east coast locations. He did not suspect primary epilepsy, which is the medical term for recurrent seizures that have no known underlying cause. “Dogs with primary epilepsy tend to have their first seizure between the ages of one and five,” he says. “Certainly a dog can be younger than that. There are what we call ‘eccentric presentations.’ But puppies are more likely to have an identifiable cause for their seizures — perhaps an infection, or a metabolic condition like a liver shunt, which means some of the body’s waste products cannot properly be disposed of. They also could have been exposed to a poison (toxin) or have a brain malformation. All of these can lead to seizures.”

A primer on seizures — and how to recognize them

Simply put, a seizure is the manifestation of abnormal electrical activity within the brain. Where in the brain? “When a dog, or a person, has seizures,” Dr. Neary explains, “we know that there is a problem in the forebrain — kind of the top and the front part of that organ. And there are many different types. In dogs, the most common type are generalized seizures, which used to be called grand mal seizures. This is the prototypical seizure that people think of when they think about an animal or a person convulsing — a loss of consciousness, motor activities like stiffness or paddling, urinating or defecating during the episode, and oftentimes, excessive salivation [all of which Newt exhibited].

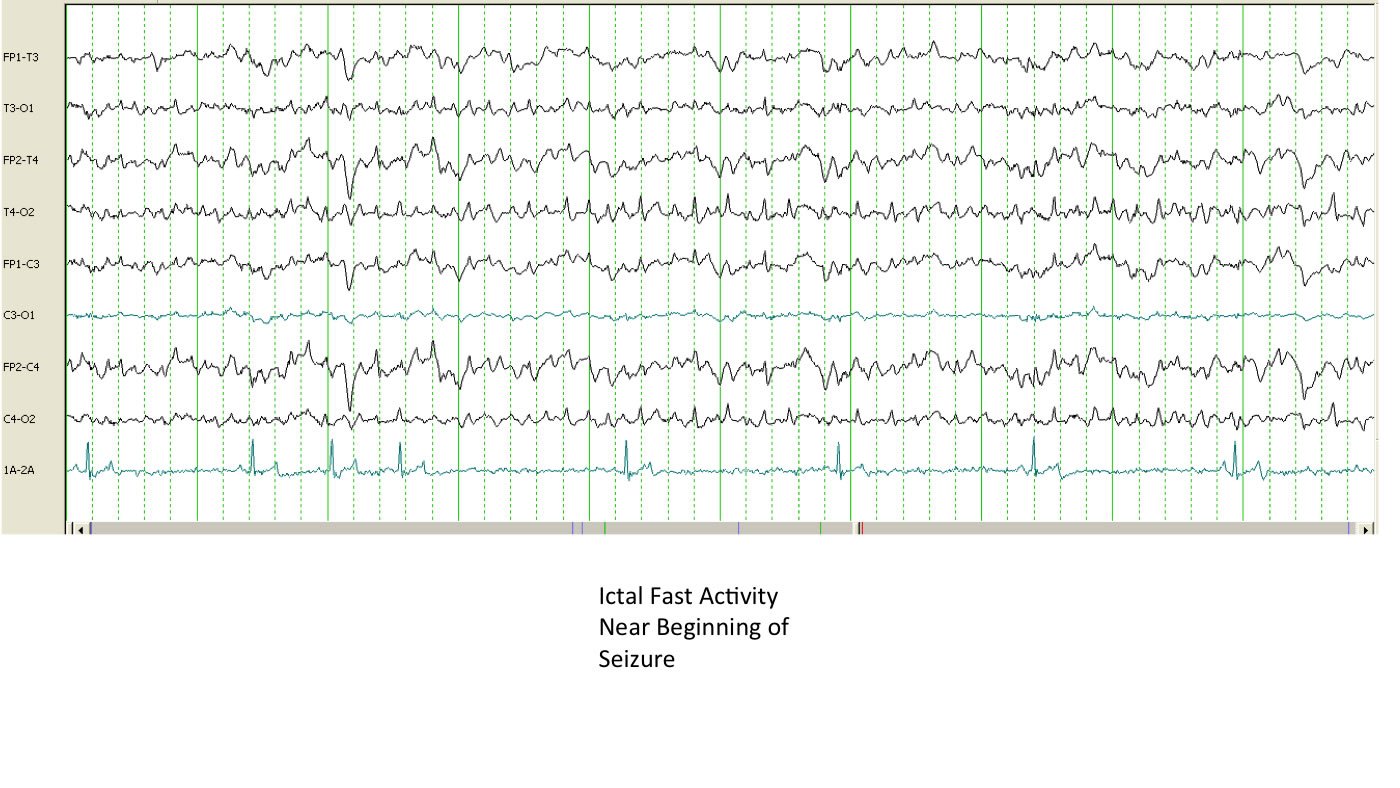

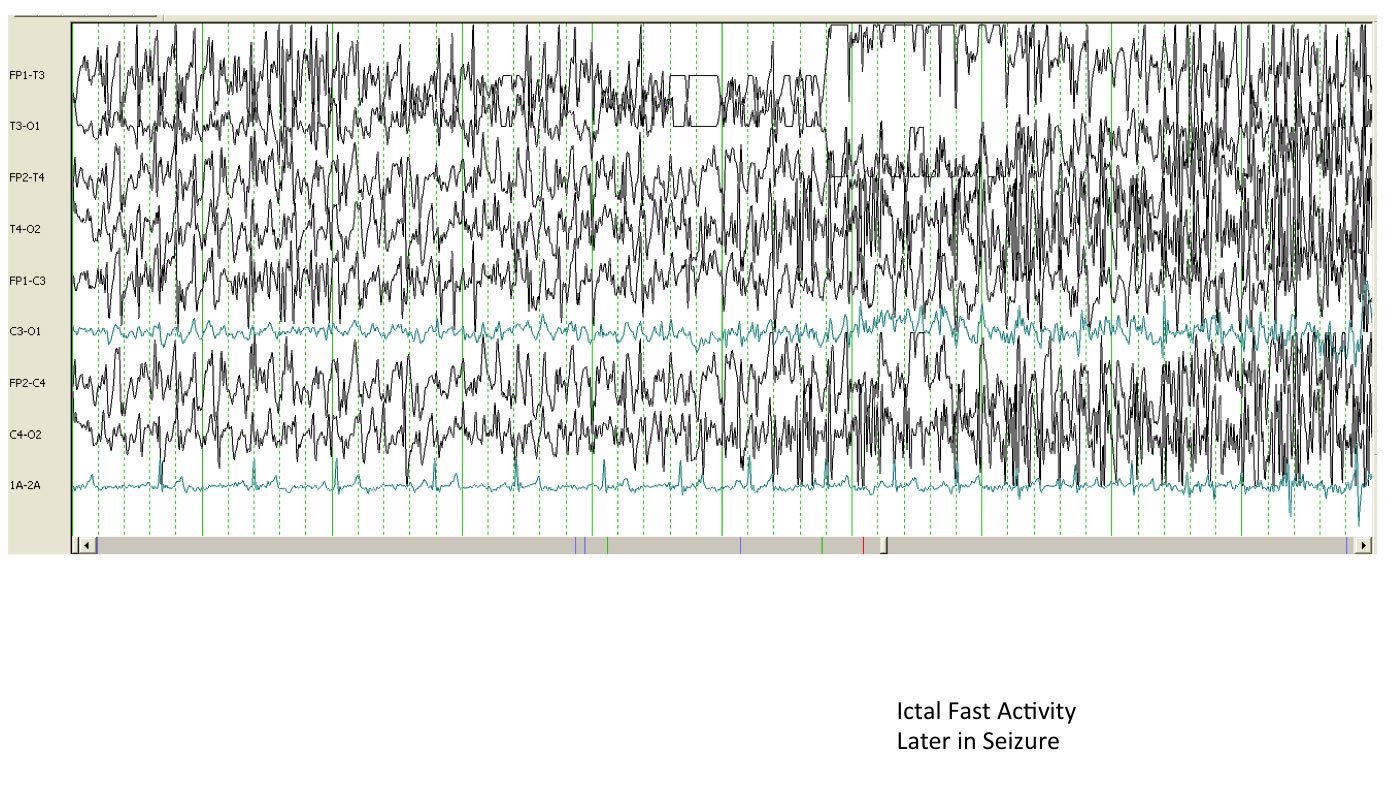

“The actual seizure lasts from seconds to minutes,” Dr. Neary says, and is followed by what’s called a post-ictal period during which the brain needs to reset. The post-ictal period (the seizure itself is the ictus) can be characterized by blindness, anxiety, wobbliness, or fear. It’s different in every dog. “Very typically,” Dr. Neary points out, “the dog will be trying to walk but is really wobbly and keeps bumping into things.”

While generalized seizures involving both sides of the brain are “the most common type that we see,” Dr. Neary comments, “there are seizures that don’t capture the whole forebrain. They are known as focal, or partial, seizures. They appear as twitching of one side of the face, contractions of muscle in one limb. Usually the affected muscle and limbs are on the opposite side of the body from where the seizure focuses in the brain.”

Whether general or partial, most seizures start in an abnormal locus of cells and then spread from there. Sometimes a seizure starts out as partial and then generalizes, crossing to the other side of the cerebral hemisphere.

Not all seizures involve alterations in consciousness. During a so-called simple seizure, the dog is still alert and aware.

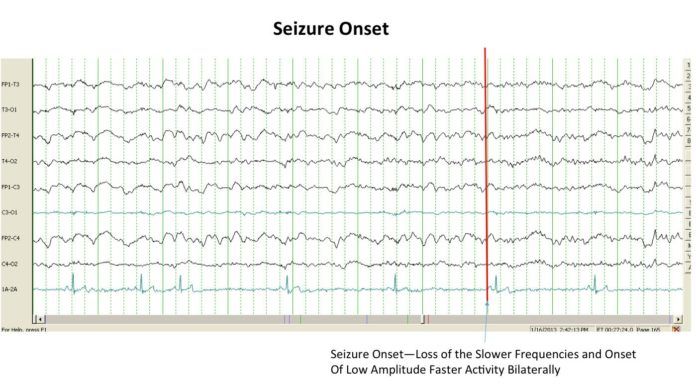

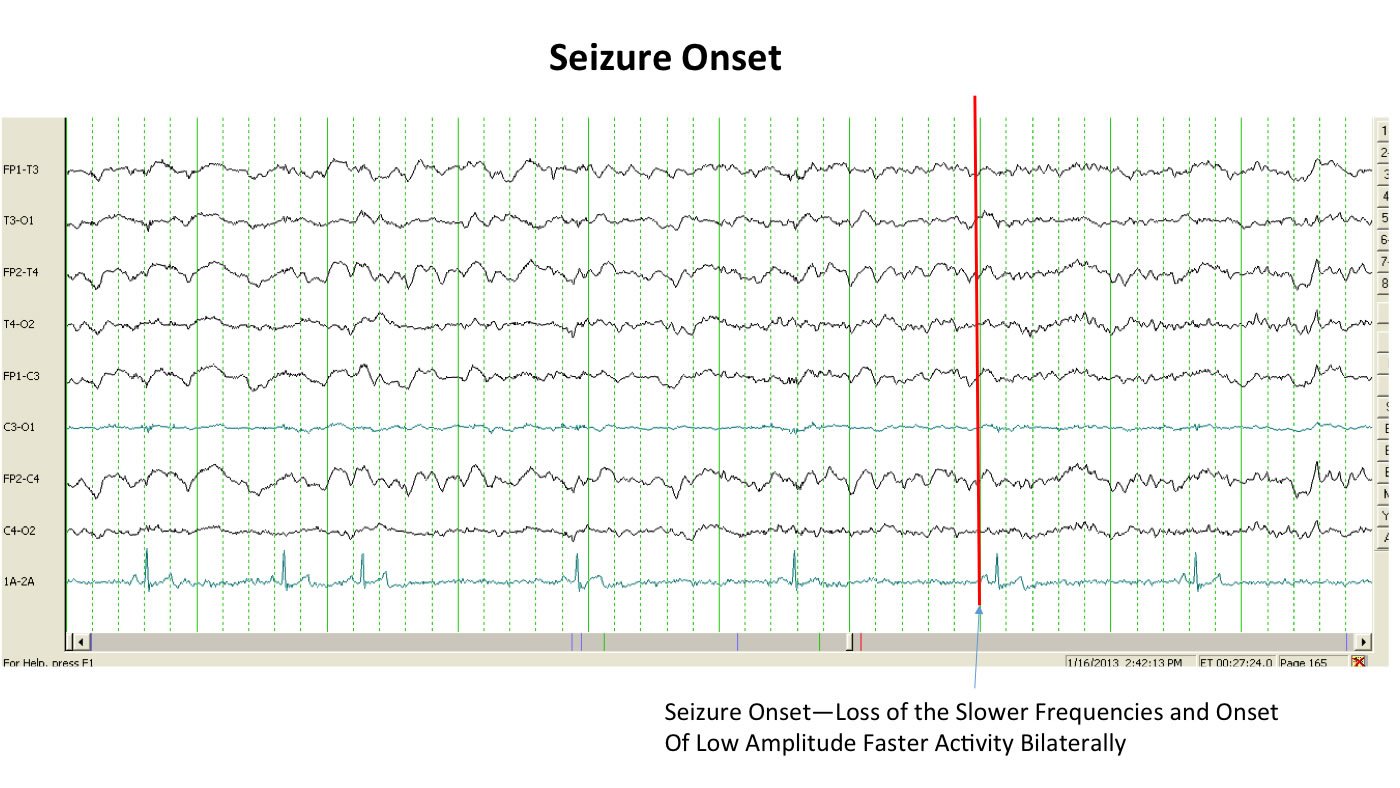

In other words, seizures vary widely in their presentations. It’s important for pet owners to know that, Dr. Neary says. “Definitively being able to declare that a dog is having a seizure is easier said than done. In fact, the only way to say with certainty is to run an EEG [electroencephalogram] during an episode and actually watch the electrical activity. Otherwise, we’re looking at a dog, or a video of a dog, and saying that looks like a seizure.”

And many things look like seizures but aren’t, he notes. Vertigo or vestibular dysfunction (a balance problem involving the inner ear) are very commonly mistaken for seizures by people, he says — understandably, because they commonly involve dizziness. Dogs with neck pain and those who have muscle spasms are also frequently thought to be having seizures when they are not, as are pets with tremors, narcolepsy (which can cause collapse and excessive sleepiness), or REM sleep disorders (which can cause excessive movements during dreaming). “You name it, somebody has mistaken it for a seizure,” the doctor says.

“Those can be frustrating cases,” Dr. Neary acknowledges. “A client will send me a picture or a video and say, ‘this is a seizure,’ and I answer, ‘well, it could be.’ It’s hard to capture even with an EEG. You’ve got to have electrodes in the scalp while it’s happening, and it may happen only once every three months.”

Fortunately, a veterinarian can make educated presumptions based on the description, or video clips. “I generally want to know whether there’s been some alteration in consciousness,” Dr. Neary says. “If the dog zones out, is not responsive to her owner, and experiences what sounds like a post-ictal period, then I’m thinking a seizure is more than likely what happened.” Generalized seizures, which include these characteristics, are easier to identify with confidence than other types of seizures, he says.

Getting at the “why”

Once a veterinarian feels confident enough that a dog is having seizures, he can begin to work to get at the cause. “I could list 100 causes of seizures for every dog that walks into my office,” Dr. Neary says. “But you can condense and customize the list based on the individual animal; it’s not the same for every dog. The animal’s age and breed help narrow things down.”

For instance, he says, “if I have a dog that’s six or older in front of me, I start thinking of older dog diseases such as a cancerous tumor affecting the brain or a stroke. Both of those can cause seizures.” Dr. Neary will especially begin to suspect a malignancy in the brain if the middle-aged or older dog is a boxer; that breed is prone to brain tumors. On the other hand, if the breed is an Australian shepherd, border collie, Labrador, or husky, his mind will go to primary, or genetic, epilepsy, that is, recurrent seizures with no known underlying cause.

To help confirm or refute his suspicions, he conducts various tests. One of them is a basic neurologic exam, an assessment conducted right in the office. If the dog is perfectly normal neurologically between seizure episodes, he will suspect primary epilepsy, which is the most common reason for seizures. If, on the other hand, the dog keeps circling in just one direction, has a visual change in just one eye, or a lack of awareness about where one of her limbs is in relation to the rest of her body and the objects around her, he will be less likely to think of generalized seizures/epilepsy and more inclined to consider stroke or a brain tumor.

Along with conducting a clinical exam right in the office, Dr. Neary will run some tests. “Basic blood work will give a metabolic picture,” he says. For instance, the doctor will learn whether a by-product of metabolism is not being properly broken down and filtered and causing issues in the brain. Blood work can also check for antibodies to infections; if they are present, or elevated, it suggests an infection may be causing the problem.

Dr. Neary will also often recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to get a look at the actual structure of the brain and see if a tumor is present, creating increased pressure inside the confined space of the skull. MRI is “also sensitive to stroke and inflammatory disease,” he says.

“If we need more information still, we’ll sometimes order a spinal tap to collect spinal fluid — fluid that bathes the brain — and evaluate it microscopically. We might be able to identify an infectious agent in the spinal fluid, such as a fungal infection. A fungus called Cryptococcus can be shed in spinal fluid, for example. Sometimes we’ll also diagnose lymphoma from a spinal tap.

“I always do a spinal tap in combination with an MRI so that we don’t have to put the dog under general anesthesia twice,” Dr. Neary says. “Also, MRI helps me identify the little pocket in the back of the head where I take the spinal fluid from.”

Dr. Neary ordered some of these diagnostic tests for Newt the terrier, specifically, blood work and MRI. Because Newt was so young, he thought he’d uncover something like an infection or a brain malformation.

Once a vet finds the cause —or doesn’t

If the veterinarian can diagnose the reason for the seizures, he can devote himself to targeting the underlying cause of the problem for treatment, and possibly a cure, rather than just managing the symptom — the seizures themselves. Once he identifies and deals with the cause, the seizures in all likelihood will cease if treatment is successful. But if he can’t find a cause for the seizures, he will make a diagnosis of primary epilepsy through the process of exclusion. That is, there’s no specific test that identifies epilepsy — it’s a diagnosis made by ruling out all other potential causes.

That’s what happened with Newt. He was one of those rare puppies with an “eccentric presentation.” The MRI and blood work ruled out any brain tumors or other disorders that would be affecting brain function, Newt’s “mom,” Ms. Strom says. “They kind of just rolled it down to juvenile epilepsy,” she comments.

Seizure treatment

When no underlying cause for seizures can be found and genetic epilepsy is diagnosed, the aim is simply to try to decrease the frequency and severity of the seizures. It’s done with anti-convulsant medications, which “are always a hot topic between vets and clients,” says Dr. Neary, “because some of the older generation drugs, while proven, have known side effects.”

These drugs include phenobarbital and potassium bromide, and their most common side effects are excessive urination, drinking, and eating along with wobbliness and sedation. “These signs are seen in 80 percent or more of the patients that are on anticonvulsant drugs,” Dr. Neary says, adding, “phenobarbital can also be damaging to the liver.”

A newer generation of anti-seizure drugs includes zonisamide and levetiracetam (Keppra). “They’ve been around in human medicine for more than 10 years,” Dr. Neary points out, “but have come into use more recently for dogs and other animals. Both of them are relatively devoid of side effects and, in my opinion, are as effective as the others at treating seizures. But every animal responds differently, so sometimes we have to go to the older medications.”

That was the case with Newt. In fact, no single medication alone was going to do it. His was a refractory case. With just the phenobarbital first prescribed by the vet, his seizure incidence did not lessen — not even when he was moved from a half dose twice a day to a full dose twice a day. Only when Dr. Neary added twice daily zonisamide to the regimen did Newt’s seizures stop. When we went to press with this article, it had been a full three months since he experienced one. Even if he has one here and there going forward, which many dogs with epilepsy do once they are diagnosed and treated, it won’t be the end of the world. It’s persistent seizures that can cause serious problems.

Will he ever grow out of his juvenile epilepsy? After all, he’s still just a pup. “We don’t know,” Ms. Strom says. “He might have the condition for life, and he might not. I’m happy because some of the things he could have been diagnosed with, like cancer, might have been deadly.”

Dr. Neary is happy, too. If left untreated, epilepsy usually worsens over time. And even a pattern of seizures that last a short time creates tremendous stress on the brain, lungs, and other organs. Body temperature can rise, too, from all the muscle activity associated with the tremors. Granted, a dog like Newt, even with his seizures under control, has to go in for periodic blood tests to check his liver function because of the phenobarbital, but he’s fine.

Well, maybe “fine” is the wrong word. “He’s a horrible puppy,” Ms. Strom says. “Whatever you try to discipline him for, he doesn’t care. You know, terriers are just like that, anyway. But he’s the ultimate terrier I’ve ever had. And I love him to death.”