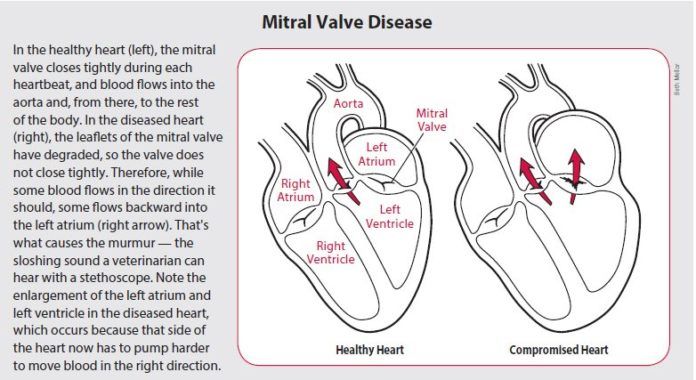

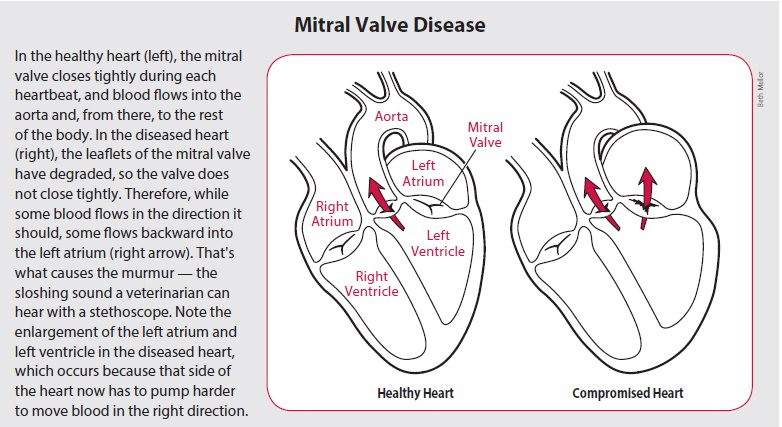

Unlike for most people, heart disease for dogs is not about heart attacks resulting from clogged arteries attributable to excessively rich diets, extra pounds, and lack of physical activity. Most often, it’s about a genetic predisposition to a faulty mitral valve — the valve that separates the left ventricle from the left atrium. Irregular thickening and shortening develop at the valve leaflets that blood passes through, and that keeps the valve from closing as tightly as it should during each heartbeat, causing some of the blood that should be moving forward through the heart and on to the rest of the body to regurgitate, or leak backwards. The left side of the heart then has to work even harder to pump blood to the body, so that the left side becomes enlarged due to the excess labor it has to perform.

Finally, the extra work isn’t enough. Too much blood keeps flowing backwards, even towards the lungs, and the lungs end up filling with fluid from the leaked blood. The condition, known as pulmonary edema, is the characteristic symptom of congestive heart failure, whose clinical signs include weakness, loss of appetite, a chronic cough, fainting, lethargy, and, finally, death.

A number of medications have been developed that successfully keep lung fluid in check while easing the heart’s burden. Thus dogs, like people, can often live with congestive heart failure for quite a while (albeit gradually becoming weaker and weaker until they succumb).

But what if there were a medicine that could help dogs stay healthy even before they developed congestive heart failure? What if a drug agent could stall the process that takes the dog from an enlarged heart to actual symptoms?

According to the results of newly published research involving not just Tufts but also 35 other centers in 11 countries on four continents, there is. Veterinary scientists at facilities in nations ranging from the United States to the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Italy, and a number of other countries have just published the results of the largest gold-standard heart disease trial on small animals (all dogs) ever conducted and found that a drug used to help control the symptoms of congestive heart failure once they appear can actually stall its development in the first place by an average of a year and four months — no small chunk of time in a dog’s life to be free of debilitating symptoms like fatigue, constant coughing, and loss of quality of life in general.

Putting the drug to the test

The drug at issue is called pimobendan, which improves the ability of the heart muscle to pump and therefore move blood in the right direction without too much cardiac stress. It has only been on the veterinary market in the U.S. for about 10 years, with studies having shown that it improves not only quality of life in dogs with congestive heart failure but also survival times. (In Japan, it is also allowed for use in human medicine.)

Recently, scientists have begun wondering if pimobendan can help once the heart has already started to enlarge because of the extra work it needs to do to pump blood forward but before the telltale fatigue, loss of appetite, and general malaise of congestive heart disease begin. To get at their thinking, consider that veterinarians slot heart disease for dogs into four stages:

Stage A: The dog is at increased risk for heart disease, perhaps because of her breed, but there is no evidence that it has begun to take hold.

Stage B: This is a long period that can last years and is split into two sub stages, B1 and B2. In the B1 stage, the veterinarian hears a heart murmur with a stethoscope. The murmur, a kind of sloshing sound, means blood is not flowing uniformly in the direction it should. The dog has no symptoms. In the B2 stage, the doctor not only hears a murmur but upon ultrasound finds heart enlargement to compensate for the backwards flow. There are still no clinical signs of disease. A person would not know her dog had heart problems just by observing her pet.

Stage C: The signs of valvular heart disease become apparent. The dog has a persistent cough, difficulty breathing, noticeably less tolerance for physical activity, and may not be as interested in eating as formerly. At this stage, pimobendan (but also a number of other medications) can help keep symptoms in check and both increase a dog’s quality of life and length of life.

Beth Mellor

Stage D: The congestive heart failure is refractory to treatment. The valve has become so compromised and the heart so enlarged that no drug therapy can minimize symptoms.

Veterinary investigators have been wondering whether administering pimobendan starting at stage B2 rather than at stage C would make a difference, that is, when the dog has a murmur and her heart has enlarged but before signs noticeable to her human family members would become apparent.

To test their theory, they organized a clinical trial with the acronym EPIC, for “Evaluating Pimobendan in Cardiomegaly” (abnormal enlargement of the heart). Specifically, they followed more than 350 dogs with an average age of nine. Almost half were Cavalier King Charles spaniels. (That delightful breed is riddled with valvular heart disease; 42 percent of Cavaliers are born with a genetic ticking time bomb to develop this fatal condition, usually dying in late middle age rather than old age). Other breeds represented included Dachshunds, miniature schnauzers, poodles, Yorkshire terriers, mixed breeds, and some other pure breeds.

All the dogs were in stage B2 of heart disease, meaning they had a murmur with a grade of at least 3 (the scale runs from 1 to 6, and grades 1 and 2 are so minor that they often can’t be heard) and imaging work that showed their hearts were already enlarged. But in the main, they did not have any clinical signs of disease.

They were either given pimobendan as chewable tablets twice a day or a placebo that looked exactly like the drug. The researchers and the dogs’ owners were all blinded — no one knew who got what — making this what scientists call a gold-standard trial that could not be influenced by perception of sickness or health rather than fact. All the dogs were then followed until they either developed clinical signs of congestive heart failure or died of it or were euthanized by their owners as a result of heart failure that diminished their quality of life.

Promising Outcome

The result: most dogs in both groups did not die over the course of the study, whether in the drug group or the placebo group. But for the dogs treated with pimobendan, it took an average of 1,337 days to show signs of congestive heart failure, versus only 846 days for those in the placebo group. That’s a difference of 491 days, or just about 16 months and a “substantial clinical benefit” say the researchers, who published their findings in the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Moreover, over the course of the study, which lasted several years, dogs treated with pimobendan were almost 35 percent less likely to even reach the point of having congestive heart failure (or dying of it).

How soon will administering the drug before symptoms appear become common practice?

The researchers write that the trial shows, for the first time, “convincing evidence” of the benefit of treatment before the onset of congestive heart failure in dogs whose hearts are already enlarged and who already have at least a moderate murmur. “The treatment effect of pimobendan was robust,” they say.

Given the strength of the results, if your dog has a heart murmur and an enlarged heart but does not yet have signs of congestive heart failure, it would be a good idea to show your veterinarian this article and talk with him about putting your pet on pimobendan at this stage of the game. Indeed, the investigators ended the study early because the evidence of benefit was so clear that they believed it would have been unethical to continue to withhold pimobendan from the placebo group.

Says lead researcher Adrian Boswood, MA, VetMB, MRCVS, DVC, of the University of London’s Royal Veterinary College, “the message that we are promoting is that we should no longer ‘watch and wait’ with dogs that are known to have or are suspected to have mitral valve disease. Since previously, treatment was widely accepted to be effective only after the onset of clinical signs, waiting until signs developed was an effective monitoring strategy. Now that treatment has been shown to be effective earlier, it is necessary to consider more actively examining patients [who have developed a significant murmur] to see if they are at a stage where they will benefit from treatment. This requires them to undergo diagnostic tests [specifically, imaging of the heart] that will allow enlargement of their heart to be identified.”