Consider how you would feel if you believed yourself to be alone and then suddenly felt a hand on your back. Or if you didn’t see any cars coming and stepped into the road, not having heard an auto screeching toward you from just around the corner. That’s how it is for deaf dogs, either because they were born that way or lost their hearing over time.

There are a lot of them out there. According to the American Kennel Club, about 5 to 10 percent of dogs in the United States are deaf in one or both ears. Deafness that’s genetic has been identified in at least 80 breeds. White pigmentation is most often linked with the condition, but that doesn’t mean a dog has to be all white, or even mostly white, to be genetically predisposed. The merle gene, found in collies, dappled dachshunds, American foxhounds, and other breeds, produces mottled spots of color all over a dog’s body, often leaving only some white, but still increases the chances for a dog to be deaf. It’s the same for the piebald gene. Distributing discrete patches of non-white fur on an otherwise white coat, sometimes so large that only bits of white show, it, too, is connected to deafness. The piebald gene is found in Samoyeds, greyhounds, beagles, and Dalmatians — a breed in which deafness is common enough that breeders are actively working to weed out potential carriers through selective breeding.

How does genetic deafness happen? Some time during the first few weeks of life, puppies who have the gene mutation for deafness do not get the right flow of blood to the cochlea — a part of the inner ear that produces nerve impulses in response to the vibrations of sound. The sensitive nerve cells of the cochlea subsequently die. Researchers say the process gets set up during fetal development.

Of course, not all dogs of predisposed breeds are deaf. On the flip side, a dog doesn’t have to be among the breeds in which deafness is more prevalent not to have the sense of hearing. And deafness can occur in a hearing dog at any time, whether because of a severe infection in the ear canal or the simple loss of hearing that comes with old age.

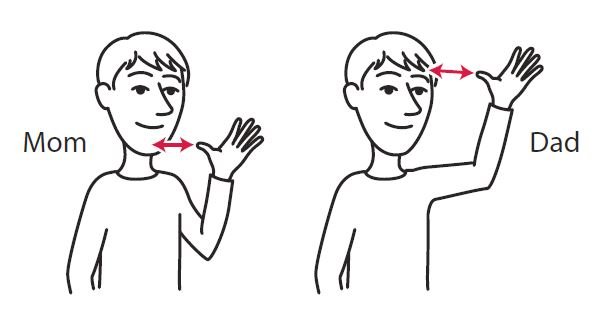

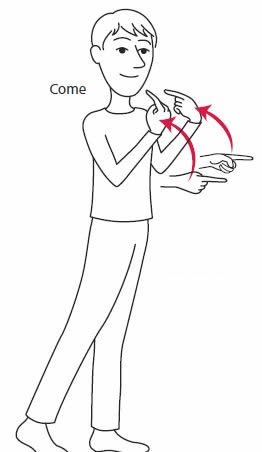

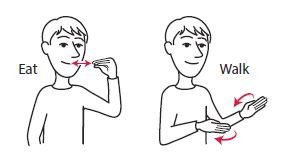

The illustrations throughout this article are examples of American Sign Language that you can teach your dog to understand.

Perhaps your own dog is one of those who has lost her hearing, or much of it; she no longer looks in your direction when you call to her. Or maybe you’ve found a deaf dog through a rescue organization and fallen in love but are concerned about how you would accommodate her. As it turns out, there are simple measures you can take to maintain a wonderful relationship with a deaf or hard-of-hearing dog — keeping communication open despite not being able to talk to her and making sure she stays safe when the two of you are outside together.

1 Keep empathy front and center. To do right by a deaf dog, you have to understand her perspective. For instance, touching her from any spot where she cannot see you coming is jarring and unsettling. Over time, this can contribute to a startle reflex because she will become uneasy about what might happen while she is simply resting. Instead, get close to your dog only from in front of her, where she can see you. Or signal her from behind by flicking the light switch a couple of times.

It’s also important to wake a sleeping dog before you leave the house to let her know you’re going. Think about how you might feel if you fell asleep with the comfort of companionship only to wake and discover you were alone. Wake your dog in a calming manner so that she can see you’re leaving without feeling anxious.

Teach your children appropriate behavior, too. While dogs are often not fans of rambunctious behavior, at least hearing ones can ascertain from kids’ laughter and other sounds that it is intended as play. What a deaf dog mostly takes in, on the other hand, are thumping and banging vibrations that she cannot make sense of. Once children are aware of how their active play can unnerve a dog, they will recognize that it’s only fair to take their energy outside or someplace where it won’t stress their pet — or perhaps include her in the fun and raucus activity.

2 Up your safety game. A deaf dog must always be kept on a leash when you go on walks in unconfined spaces that don’t have fencing. A leash connected to your hand will keep your dog safe from fast-moving bicycles or joggers that suddenly zoom near. While a hearing dog will jump out of the way, a deaf dog will not even have a chance unless you are vigilant for her and keep her close to you.

Do not imagine that you can or should try to train your dog to run freely outside of a fenced-in area, say, on a wooded path. It is far too easy for a dog to tear off after she sees something of interest, and you can’t call her back to you if she goes out of sight, leaving her unprotected from people and other animals she may encounter.

Of course, accidents happen, and your dog can break free of your grasp. That’s why it’s a good idea to fasten bells to her collar so you can at least discern the general direction she has gone. And make sure to attach not only tags with contact information but also a tag that states she is deaf in case someone else finds her.

3 Speak in sign language. In Deaf households where American Sign Language (ASL) is used, dogs come to understand signing in much the way dogs in hearing households learn to make sense of vocalized speech. That is, they look for particular words that denote meanings they’re interested in, such as “walk” and “eat.” Dogs do not have a language center in their brain, explains Stephanie Borns-Weil, DVM, the Head of the Tufts Animal Behavior Clinic. Rather, they use words as cues. The sound of a particular word lets them know it’s time to go out or come to the kitchen for their food. So it’s an easy enough “translation” from the spoken word to the signed word to get different cues across.

What dogs also get as you convey information to them, Dr. Borns-Weil says, is the overall mood of your message and the degree to which they are part of the family. When the word is spoken, it’s about a joking or cooing manner. But it’s just the same with sign language because it consists not only of hand movements but also overall body movements and facial expressions that convey a fuller context. Your general demeanor and love for your dog will come through, and life for her will not be an isolating and deadening experience.

While the illustrations on these pages show some words in ASL that you can use in conjunction with your loving manner, it doesn’t have to be ASL. You can make up your own hand signals to communicate with your dog if you prefer.

4 Don’t neglect training. Training is no less critical for a deaf dog than a hearing one. In fact, in certain situations, training a dog to respond to a sign to “wait” can save her life.

“The same rules apply to training with sight as to training with voice,” says Dr. Borns-Weil, herself the owner of a deaf dog she recently rescued — 12-year-old shih tzu Dick-ens. “The command should be clear and consistent.”

Dr. Borns-Weil is all for ASL if people want to use it with their deaf dogs. But she has created some of her own “signs” to communicate with Dickens. For example, when cueing him to “come,” she holds her right arm out with her elbow bent at 90 degrees and then flaps her hand in a downward direction. When she wants to let him know he has been a good boy, she gives him a “thumbs up.”

“The more cues a dog knows, the more understandable and predictable their environment is,” the doctor says. But it’s important not to overwhelm. If you’re teaching your deaf dog sign language, whether your own or ASL, keep the training sessions to no more than a few minutes at a time, a few times a day. And make it a cause of enjoyment — cues combined with treats for getting it right.

Training will help your deaf dog learn to do everything you’d want a hearing dog to do — not rummage through the garbage looking for food, not gnaw on chair legs, come on over for a soothing belly rub, and so on. It will be a happy, well ordered (well, fairly well ordered, as with most dogs) life.