You know you should be assessing your dog’s body condition score to make sure she’s not too heavy by looking at her from above so you can easily see and then feel her waist and an abdominal tuck. You should also be able to feel her ribs very easily when you lightly run your fingers over her sides. But the body condition score assesses only your dog’s fat stores. What about her muscle condition score? Your dog can be just the right weight, or even overweight, yet have too little muscle.

Why is that a problem? It’s because dogs with muscle loss are often weaker than they should be and may have depressed immune function and a diminished ability to recover from illness, surgery, or injury.

In its broadest terms, muscle loss comes under one of two headings: cachexia or sarcopenia. Cachexia means the muscle loss is the result of a chronic disease such as heart failure, long-term kidney disease, or cancer. In one study at Tufts, more than half of dogs who had congestive heart failure were found to have some degree of cachexia. A separate study found that one in three dogs in the very early stages of cancer had cachexia. Cachexia also covers muscle loss from injury or acute illness. It can all be a vicious cycle; an animal loses muscle because of an illness or injury and then has a hard time recovering from the problem because of the negative effects that cachexia causes.

Sarcopenia, a term coined at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, is muscle loss associated with aging in the absence of disease, and it applies to dogs as well as people. One research study on a group of Labs assessed from eight weeks of age till death identified a significant loss of muscle during aging. Other studies of dogs showed similar results. Across the board, it appears that as many mammals age, their muscle mass diminishes, often with an increase in fat mass, that keeps total weight constant or even increasing. And the muscle that remains doesn’t function as well as it used to. While it’s not a disease state, neither is it desirable. As with cachexia, sarcopenia comes with a loss of muscle strength and increased risk for physical disability. Note that cachexia and sarcopenia can occur together because older dogs are at increased risk for diseases associated with cachexia.

More and more dogs are experiencing sarcopenia because more and more dogs are living longer. More dogs are also falling prey to cachexia due to disease conditions that are more likely to occur as they age. The longer the lifespan, the higher the chance that a disease that involves muscle wasting, such as cancer, will take hold.

Muscle loss, no matter what the cause, may or may not be related to appetite and how much a dog is eating. It also does not correlate with whether a dog is overweight or underweight. A dog may be eating the same amount she always has and can even remain at the same weight yet still lose muscle. In other words, assessing whether your dog is ideal body weight from the body condition score will not tell you about the state of her muscle mass. For that, you need to do a separate evaluation.

Hands-on: assessing your pet’s muscle condition score

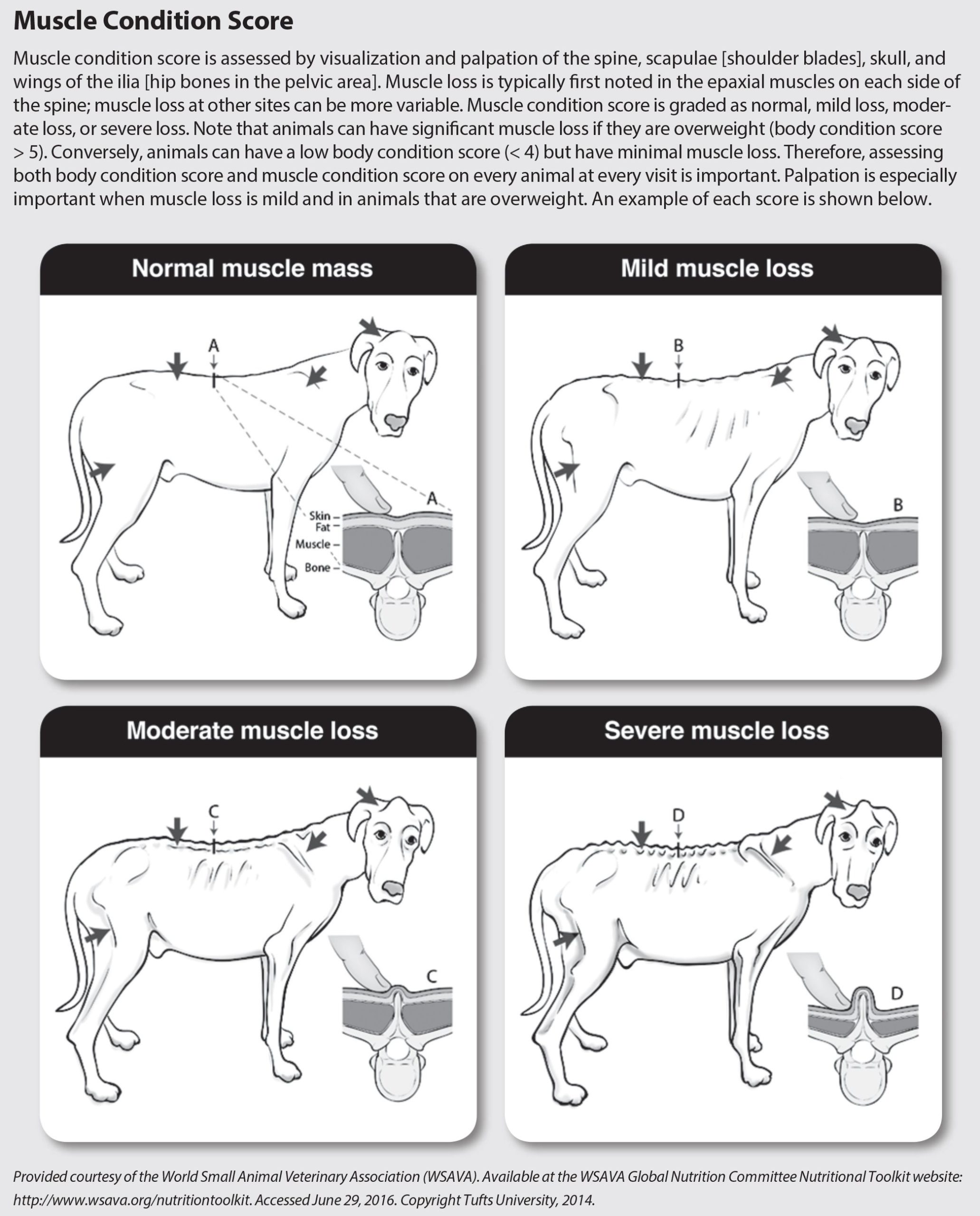

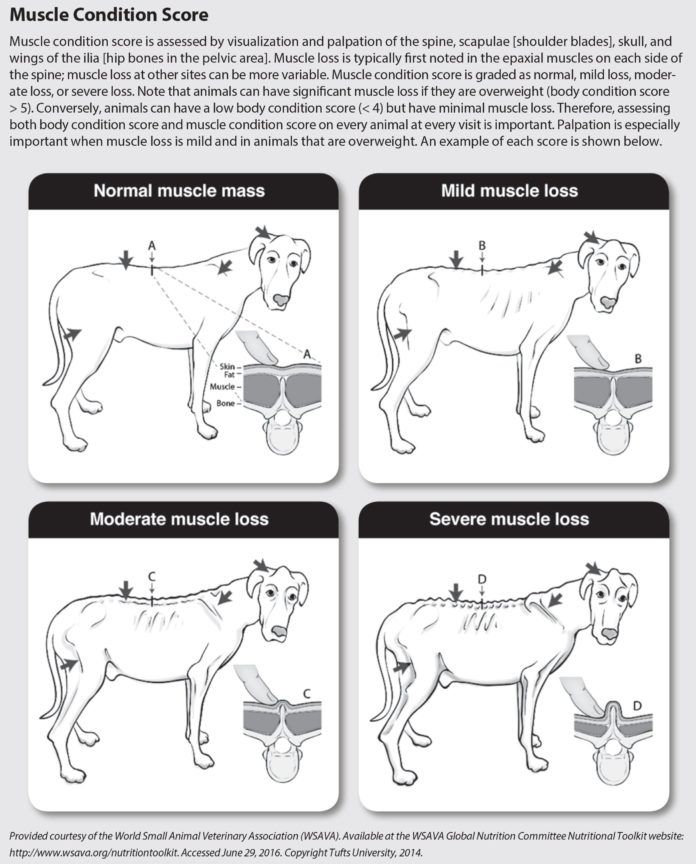

The World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) has specific guidelines for assessing whether your dog’s muscle mass is adequate in its nutrition toolkit (wsava.org/nutritiontoolkit). The muscle condition score chart was developed by Lisa Freeman, DVM, PhD, DACVN, Director of the Tufts Institute for Human-Animal Interaction, when she served as co-chair of the WSAVA’s Global Nutrition Committee. Your pet can have one of four muscle condition scores: normal muscle mass, mild muscle loss, moderate muscle loss, or severe muscle loss. In all cases, you check the spine, scapulae (shoulder blades), skull, and wings of the ilia (the muscle around the pelvis).

It’s a matter of both looking and feeling. First check the spine, where muscle loss initially tends to be observed. You’re looking specifically at the muscles along each side of the spine, which are known as the epaxial muscles. The epaxial muscles normally make it so that you can barely feel the tips of the spine if you run your fingers down the center of your dog’s back. As dogs lose the muscle on the sides of the spine, however, the spine becomes more prominent, and you can more easily feel it when you feel along the center of your dog’s back. Similarly, your dog’s hip bones and shoulder blades become more easily felt. Some dogs also lose muscle over the top of the head, making it feel bonier.

Palpation (feeling along these spots) is especially important for a dog who is overweight or has a medium or longhaired coat; you have to get down below the fat —or thick coat — to feel the muscle beneath.

When your dog is young, checking her muscle mass frequently isn’t so critical. But in the later years, starting at middle age based on the expected lifespan for your dog’s breed, you’ll want to be assessing her muscle mass a couple of times a year, just as you’re supposed to be assessing her body condition and making sure she’s at ideal weight. The earlier you catch a trend toward muscle loss, the better treatments will work to keep the process from speeding up. Sometimes treatment can even reverse the condition. If your dog actually has a condition that causes muscle wasting, such as congestive heart failure, kidney disease, liver disease, or cancer, you’ll want to check her muscle condition score even more frequently. It’s much easier to maintain the muscle mass that’s there than to reverse losses.

Keeping further muscle loss at bay

There are a number of things you can do, with a veterinarian’s supervision, to help stave off muscle loss in a sick or even an aging dog. They fall into the realms of physical activity and feeding.

Exercise. You’ve heard 1,000 times that exercise helps build muscle, and it’s as true for dogs as it is for people. The thing is, with an older dog or one who is laboring under a serious medical condition that’s causing her to lose muscle mass, you’ve got to be careful about how much exercise you add to your pet’s daily routine and how vigorous it’s going to be. A dog, like a person, cannot safely go from being a couch potato to an athlete. Check with your veterinarian to determine the amount of exercise that’s appropriate. And don’t feel discouraged if your dog can’t handle a lot. Even going from lying around all day to taking two 1-mile walks can have an effect — again, as long as your pet can safely take on the additional physical activity.

Nutrition. Depending on the situation, a veterinary nutritionist might be able to make changes in your dog’s diet to help stave off muscle loss. Do not decide on your own that the answer is to feed your dog more protein. While muscles are indeed composed of protein, it’s not as if the protein we eat goes directly to our muscles. It’s more complicated than that. Also, more protein is not always better; in some cases it can compromise a dog’s health even further. However, it is critical for your dog to have enough protein.

Consider kidney disease. Kidney disease can definitely contribute to muscle wasting, but the kidneys of a dog with this condition cannot properly handle protein. For that reason, dogs with kidney disease need to have their protein intake carefully adjusted and monitored based on the type and severity of their illness, with the veterinarian monitoring the dual problems of muscle loss and kidney failure. It’s tricky. Early on in the disease process, too much restriction of protein contributes to muscle loss, and later, too much protein compromises the kidneys. It requires ongoing medical assessment. Your veterinarian, preferably with the input of a veterinarian who is board-certified in nutrition, can keep tweaking the diet over time.

Note that with aging, a common mistake that can impact muscle mass is to automatically change dogs to a “senior diet.” Senior diets have no legal requirements for containing nutrient levels that differ from those in diets for adult dogs that are not yet geriatric. So “senior” nutrient concentrations can vary dramatically depending on the brand and individual product. Indeed, some dogs lose muscle as they age because their owner has changed to a senior diet that has reduced protein levels or that is lower in calories than their previous diet.

One of the most important things you can do if you detect muscle loss in your aging dog is to provide your veterinarian a complete list of everything your dog eats — dog food (specific brand, product, and flavor, or the exact recipe if you feed a home-cooked diet), treats, table foods, home-cooked supplements, rawhides (or similar products), dental products, and foods used to administer any medications your dog is getting. This allows the doctor (or a veterinary nutritionist) to assess whether your dog’s diet is nutritionally balanced and has the right amount of calories, protein, and other nutrients for your dog’s age, activity level, and any medical conditions. Providing this information is even more important if your dog has a medical condition causing cachexia because then it can be used to fine-tune the diet to meet all your dog’s nutritional needs.

When your dog has cachexia, it’s also important to maintain her appetite. Many dogs with cachexia eat less food or become pickier about their food so it becomes more difficult to get them to eat enough calories. And if they don’t ingest the right amount of nutrients in the calories consumed, that will accelerate their muscle breakdown.

One way of insuring adequate calorie and nutrient intake is to get a list of multiple dog foods from your veterinarian that are nutritionally optimal given your pet’s particular condition so that if her appetite fails on the first food, you can move on to another and see if that entices her to eat. Dogs with heart failure or chronic kidney disease often have “cyclical” appetites. They’ll eat something for a few days or a couple weeks, then become disinterested in that food but will eat another option well. They’ll usually come back to the original diet, so having three to four appropriate diets that you can rotate through is helpful. Smaller, more frequent meals may also increase food intake, as can flavor enhancers. Some dogs prefer meat flavors, while others like sweet ones that can be had in flavored yogurt, maple syrup, or applesauce. Again, the food must be compatible with the dog’s condition. A dog with muscle wasting from heart failure (cardiac cachexia) needs to avoid foods that are high in sodium, as some flavored yogurts are.

Sometimes not a change in food but a change in food temperature does the trick for a dog with muscle loss who is having trouble working up an appetite. While cats often prefer foods warmed, dogs are more variable in their preferences. Some like it hot, others at room temperature, and others still, cold or even frozen. Feeding a dog on a dinner plate rather than from her usual bowl, perhaps in a different spot than usual, may also pique interest — and appetite. It’s really important to try to get a dog who is losing muscle to eat enough calories, in part because muscle loss itself can exacerbate a disease state but also because a lot of owners think it’s time for euthanasia when their dog is no longer interested in food when there may be strategies to address the decreased appetite.

Of course, it also needs to be determined whether a dog has dental disease or pain somewhere in her body, both of which can diminish appetite in addition to a particular disease, and both of which can be corrected, or at least attenuated, with dental surgery and pain medications. A decrease in appetite in a dog is always a signal for a checkup from your vet to be sure there are no medical issues contributing to the reduced interest in food. This is true even in dogs who have diseases that have already been diagnosed, such as kidney or heart disease, because a decrease in appetite in a dog who has been eating fine may signal changes in the condition that require treatment adjustments.

Apart from maintaining appetite to maintain muscle mass, a veterinarian may also advise trying fish oil supplements, which are high in a specific type of omega-3 fatty acid. In at least one study at Tufts conducted by Dr. Freeman and colleagues, fish oil supplements were shown to actually decrease muscle loss in dogs with congestive heart failure. It is believed that omega-3s interfere with the action of inflammatory substances in the body called cytokines, which can contribute to muscle loss through a metabolic mechanism.

Appetite stimulants like mirtazapine and cyproheptadine may potentially benefit some dogs, too, although the effect tends to be minimal. Feeding tubes, on the other hand, can prove a tremendous benefit in dogs with chronic diseases such as kidney disease. Not only is inserting a feeding tube a way to provide all the calories your dog needs to minimize muscle loss, it also provides an easy way to give your dog the optimal diet for her individual needs when her appetite is lacking. Many owners think of feeding tubes as “end stage,” but they shouldn’t. Placing a feeding tube early in a dog with a disease affecting appetite can be extremely beneficial. Consider that relatively early placement of a feeding tube typically affords a dog more quality time than waiting until she has end-stage disease with severe debilitation.

Treatments on the horizon

Muscle lose through illness (cachexia) and muscle loss through aging (sarcopenia) are so common in people that drug companies are working to bring to market medications that can be used to treat or even prevent muscle shrinkage. Since drugs for people often then become drugs for dogs (and vice versa), veterinary nutritionists are hoping that someday, perhaps not too far down the road, veterinarians will have pharmaceutical options in their toolbox along with exercise and nutrition protocols in order to help dogs forestall the loss of muscle that can make a sick or aging dog more feeble and less able to fight disease. One drug has already been approved as an appetite stimulant in dogs (but is not yet available)— Entyce (capromorelin oral solution).

Researchers are also looking at whether drugs can be developed that can modify the metabolic mechanisms in cells that cause the breakdown of muscle; influence hormones that affect appetite so that dogs in danger of losing muscle from not eating enough can have their appetites stimulated in new ways; and even enhance the synthesis of protein from the building blocks available in the body. Stay tuned.

I’m confused by how to ‘rate’ body muscle mass. I have a puppy. I am trying to fill out a form that has a scale 1-10.