Do you have a dachshund with a moderate or severe spinal cord injury? Texas A&M University’s College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, about 90 miles from both Houston and Austin, wants to study your pet to better understand the illness and begin to figure out ways to treat it.

How about a dog with diabetes who has to take insulin twice a day? Washington State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, a couple hundred miles from both Seattle and Boise, wants to see if transplanting insulin-producing stem cells into your pet can cure the disease or at least significantly reduce her need for insulin. Researchers there are even going to look at whether this new therapy can reverse diabetes-related organ damage.

Maybe your pet has congestive heart failure resulting from mitral valve disease, the most common type of heart disease to strike dogs. If so, the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University wants to test a new drug in your dog to see if it can reduce muscle loss that comes with heart failure and, in so doing, maintain your pet’s strength and immune function and even overall survival.

And at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Florida, investigators are recruiting dogs for a clinical trial to see if a new immunotherapy treatment can help with an all too common skin ailment called atopic dermatitis, which affects one in 10 dogs. It causes itchiness so awful and incessant that it frequently leads the animal in discomfort to bite, lick, and rub herself to the point of developing nasty infections.

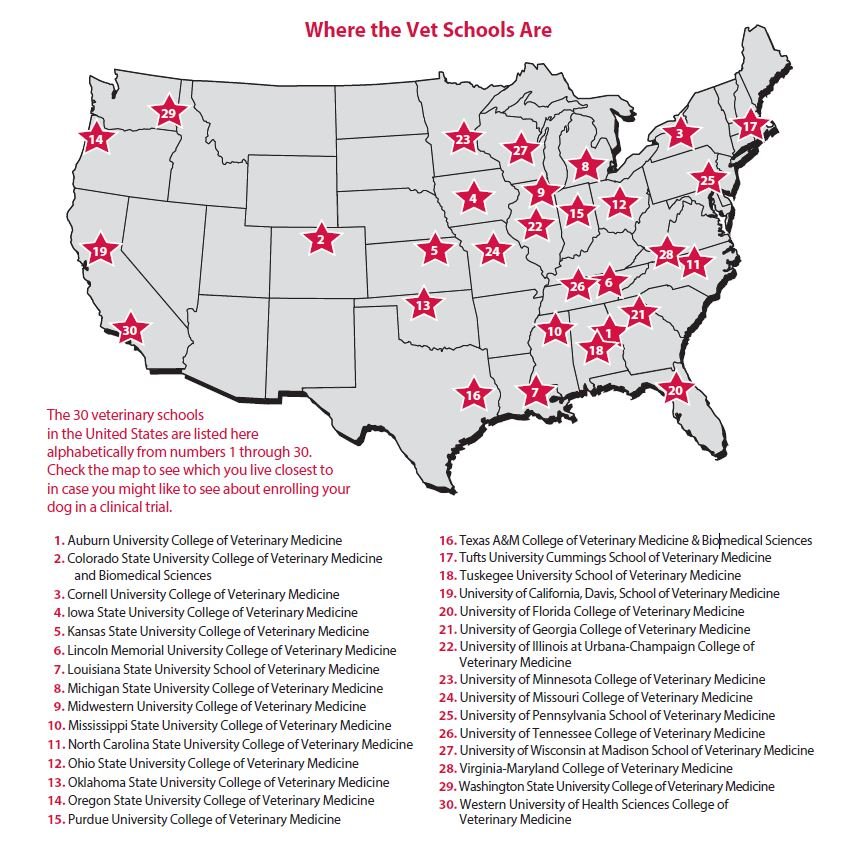

It’s not just these four schools that are recruiting dogs for clinical trials. There are 30 veterinary schools across the United States, and most, if not all, conduct clinical trials to improve dogs’ lives and lifespans. And your dog can participate in the research.

Not all of the trials are about physical health. For instance, Purdue University’s College of Veterinary Medicine in West Lafayette, Indiana, two hours from Chicago and about an hour from Indianapolis, is currently recruiting dogs for a study to better understand factors that put them at risk for social anxiety. They are also conducting a study on dogs who act aggressively toward people (as opposed to other dogs), and are looking for Labs, beagles, and standard poodles for an investigation of the genetics of behavioral triggers.

Some of the potential benefits to you and your dog for participating in these trials are obvious. But are there other reasons to schlep your pet, say, two hours from home to participate in a clinical study? Absolutely!

Win-win

Of course, if your dog has an illness like diabetes and you enter her into a trial to see if a new drug will improve management of the disease, you stand a chance of your pet coming out healthier than she was when she went in. But depending on the study, other benefits could accrue to your dog as well. That is, during the course of the research, she might also receive a treatment that’s already proven.

How is that? Consider that in many research trials, subjects are given either the treatment or drug being tested or a placebo, which means half the dogs are not receiving the possible benefit. This type of trial design is typically used when there is no known effective treatment. But, says Your Dog editor-in-chief John Berg, DVM, “a lot of trials, particularly in the area of oncology [cancer], are designed so that they don’t start out with a placebo. First, all the dogs enrolled get the current standard of care in treatment,” that is, the current best practice out there. “Then they’re randomized to receive either the new treatment being tested or a placebo. But by getting the best treatment currently available to start with, they are assured of receiving the gold standard in medical care for a very serious disease,” he says. “That way of doing things tends to be more palatable not only for the owner but also for the investigators.” Everybody involved knows that even if a dog ends up getting a placebo, he will have started out with a useful medical therapy.

In some cases, Dr. Berg says, the treatment a dog is given might normally cost several thousand dollars but as part of a trial is conferred for free, or at a greatly reduced price. That means owners who might not have been able to afford to give their dog the gold standard in treatment can now do so.

Money does not always come just as free or reduced-priced treatment. Sometimes owners receive money for enrolling their dog in a clinical trial. “How much financial support there might be varies quite a bit,” Dr. Berg says. “Trials funded internally from school funds tend to have small renumerations compared to what might be found with a trial sponsored by a government agency like the National Cancer Institute or a corporate-sponsored trial. Such organizations tend to have deeper pockets and can devote more money to making trials happen.” Sometimes, Dr. Berg says, renumeration can be in the hundreds, or even thousands, of dollars.

That might be part of the reason, he says, that “there are dog owners who sort of shop for clinical trials. Some might be motivated by free treatment or the opportunity for renumeration. But some,” he adds, “simply want to participate in the most cutting-edge research out there. Most studies are designed to test possible new therapies that seem promising, and they want to be in on that. So they’ll travel.”

More than a ripple effect

For some people, it’s not just about helping their own dog, or their own wallet. It’s about helping the canine population in general. “Many people welcome the opportunity to help other dogs,” Dr. Berg says. Indeed, a number of clinical trials at the various veterinary schools need “control” dogs — dogs who are not sick but who serve as a comparison to the dogs who have a health issue and require treatment.

Those who participate may also be helping other people, including those who don’t have dogs. “Some of the trials are really directed at human diseases,” Dr. Berg says. “Many of the cancer trials are like that,” he comments. “Chemotherapy, immune-modulating therapies, targeted drug therapies — a lot of times testing these treatments in dogs with cancer is an early step before testing them in people,” so by enrolling your dog in a clinical trial, you might be helping to find cures for illnesses that befall our own species.

In other words, Dr. Berg says, “everybody wins” — your own dog, you, other dogs and their owners, and sometimes, people who do not have dogs in their own lives. The information generated by the results of trials could end up having broad benefits. “Trials are a key way we make progress,” the doctor notes.

Some possible hoops to jump through

Not any dog can enter any clinical trial. Sometimes, as in the case of the Purdue University trial looking at dogs who are aggressive toward people, there are breed restrictions. Other times, there are age restrictions or restrictions around the animal’s degree of illness. In the Texas A&M research on dachshunds with spinal problems, for instance, there are strict definitions for “moderate” and “severe,” and a dog cannot be entered into the trial unless she fits into one of the prescribed categories. The dogs have to be between two and six years of age, too, and must be considered behaviorally appropriate.

Then, too, a number of trials require repeat visits to the veterinary school for follow-up testing in the form of blood work or other screenings. And some screenings may require sedation or even anesthesia. These include, say, biopsies to better understand the response of a tumor to treatment, or imaging to determine whether a cancer has metastasized. Federally funded and corporate-funded trials in particular “tend to be pretty rigorous about following up with patients,” Dr. Berg says, “and that can create inconvenience for the owner.” In other words, you need to be clear ahead of time about what you’re getting into so you can be sure you can follow through on the commitment. Otherwise, your dog’s participation will come to naught.

Informed consent

All trials are conducted with complete written informed consent from the owner about the risks and possible benefits of participation, Dr. Berg says. “Every veterinary school has a committee that reviews any clinical trial protocols to be sure the client consent form characterizes the trial accurately and is complete in the information it gives. In fact, the whole research project has been through a review process before the investigators get permission to run the trial and put out the word for enlisting dogs.”

To find out about clinical trials being run by a veterinary school near you, do an Internet search of the school. Then look for a tab that says “Research,” which many of them have. Often, a drop-down on that tab will list the clinical trials currently enrolling dogs (and cats, and horses). Sometimes, the Research tab won’t get you to what you’re looking for, and finding the current clinical trials on a veterinary school’s website can be difficult. But you can always put the phrase “clinical trials” in the search bar or call the school for more information. Most schools are happy to talk to people interested in having their pets participate in research that could help the canine, and potentially human, populations.

Categories of Clinical Trials

“Trials kind of break down into two categories,” says Tufts’ John Berg, DVM, a soft tissue surgeon with a special interest in certain types of cancer. One type is the non-randomized trial. That means all the dogs get the treatment, and the goal of the research is to determine whether it works and is better than existing treatments.

The other broad category is the randomized controlled trial. This is considered the gold standard in scientific research. The way it operates is that the dogs are randomly selected either to receive the treatment being tested or a placebo. These kinds of trials are often double-blind. Neither the researcher nor the owner knows which dogs are getting the treatment and which aren’t. That way, there can be no bias in determining how well the dog does in responding to the new therapy.

As stated in the main article, in more and more randomized controlled trials, all the dogs enrolled at first get the best treatment currently approved before moving on to the randomized phase in which an unproven treatment is tested. That way, even the dogs who receive a placebo will have started out getting the best medical therapy science now has to offer.

When One Study Is Conducted at Multiple Veterinary Schools

Not infrequently, a trial will be a multi-center study. Thus, if you see a trial taking place in an eastern veterinary school but live in the west, check a few of the schools closer to home. You might end up happily surprised that the same research is going on in your area.

“Some of the best, most well funded studies involve multiple veterinary institutions,” Dr. Berg says. “The greater number of dogs involved give the trial more power.

“Tufts Cummings School right now is conducting a trial on osteosarcoma [bone cancer] that is looking at the potential benefits of a cancer treatment developed at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Penn is recruiting dogs as well, as are a number of other veterinary schools, including the one at the Ohio State University.”