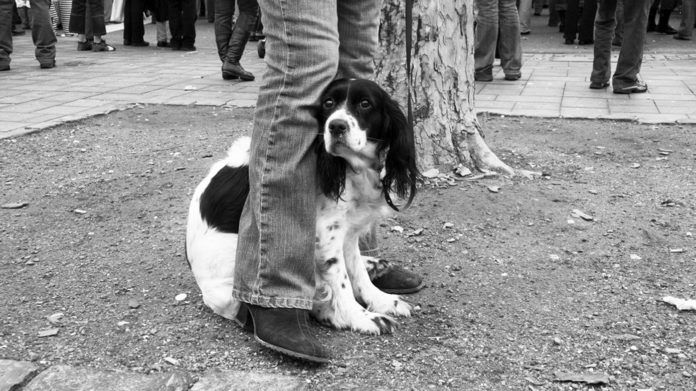

How many times have you heard people — and even many dog trainers — say that the best way to help a dog past a fear of something is to immerse her in the very thing she’s afraid of — throw her into the deep end of the pool, so to speak, where she’ll learn to cope as quickly as possible?

Istock

A worse idea for helping a fearful dog couldn’t be thought up. It’s called “flooding,” and it always backfires. Think of a dog who is afraid of other dogs and whose owner tries to “snap” her out of it by continually bringing her to a park where dogs run around freely and go right up to each other. It doesn’t work. It can be dangerous, too. A lot of fearful dogs, rather than cower, lunge; or bite; or chase. What they don’t do is get used to whatever it is they’re afraid of. Instead, they set you up for a potential lawsuit.

So what is an owner of a dog with a fear, or fears, supposed to do? The answer: reintroduce the dog gradually to what she’s afraid of in a very controlled, systematic way by staging a fake version of the real thing that’s causing her fright. All the while, you want to condition her to believe that what she thinks is scary (and perhaps is causing her to be aggressive) is anything but. In psychological terms, it’s called “desensitizing” coupled with “counter-conditioning.”

The right way to desensitize a fearful dog

“Let’s say the fear-based aggression is directed toward strangers,” says Nicole Cottam, a certified applied animal behaviorist at the Cummings School who works with clients to get their pets over various behavioral hurdles. “Someone approaches from the opposite direction, and the dog invariably begins to stiffen with a hard stare, perhaps showing her teeth and begins to growl.”

What you want to do, Ms. Cottam says, is artificially create that situation in “practice sessions” so you can “control all the variables.” That is, you have to find someone to work with you, to be the stranger approaching from the opposite direction. That way, you can tell them that they should stop “at that tree, 50 feet away” — the distance at which the dog usually starts to lock eyes but before she “explodes.”

At that juncture, Ms. Cottam explains, you take the dog and switch directions to remove her from the object of her fear. She is becoming aggressive because she wants the person to move away from her; she’s trying to scare the person away, to put distance between her and the fearsome object. So you fulfill her need for her; you create more distance between her and whatever is triggering her reaction.

It’s the same even if the fearful dog does not respond aggressively to whatever she’s afraid of. Perhaps it’s the vacuum cleaner, and whenever it goes on she dives under the couch, terrorized about an attack by the noisy “monster.” If that’s the case, don’t put on the vacuum and drag her toward it with the leash; that’s never going to get her accustomed to the scary machine. Instead, start by simply leaving it out in a corner of a room, unplugged. Gradually, she may come over to sniff it. After she has seen it many times, you might take her to a room at the other end of the house and have someone turn it on, just so she can hear it from a distance but not have to be concerned about its moving around on the floor. And so on.

Whatever is causing the fear, “there’s no one-trial learning,” Ms. Cottam says. “You have to do it 10 times in a row,” and maybe many more, reintroducing the threat little by little. And you have to include the element of counter-conditioning, or it won’t work as well.

Bigstock

Coupled with desensitization: counter-conditioning

Okay, so you move your dog away from whatever she’s afraid of — a stranger approaching on the street, a vacuum cleaner, another dog (that you’ve arranged to be the “stranger” and whose owner you’ve coordinated with about a time and place to keep all the variables tightly scripted). Gradually, ever so gradually, you draw her closer to the dreaded thing. But at the same time, you want your dog to learn that the object causing terror actually goes hand in hand with a good rather than a bad outcome. That’s the counter-conditioning part — conditioning your pet that what she thinks will cause disaster will actually prove a pleasant experience.

With an approaching stranger, for instance, your dog might feel relieved that you move in another direction. That’s a good outcome right there. But if you want to reach a point that you and your dog can actually pass someone on the street rather than walk away, you’ll want to sweeten the deal with a treat, teaching your pet to associate walking past someone with getting something desirable. If your dog is food motivated, the treat can be a tiny piece of delectable cheese or some other tasty morsel. Then she will learn, as you go through the staged appearance of the stranger 50, then 45, then 40 feet away, that a surprise encounter with a person ends with a delicious piece of food. You’ve now combined the gentle approach of keeping her far from the stranger with a feel-good sensation. What could be better?

Over time, she’ll truly begin to let go of her fear. You’ll be able to get closer and closer before giving her the treat until you can actually pass without her struggling to tug on the leash in order to scare the person away. “It’s a gradual reintroduction of the threat in association with a treat,” Ms. Cottam says, “in which you’re controlling the dose of the scary thing.” Think of it like starting in the shallow end of the pool with just the dog’s paws getting “wet” at first, then moving further and further toward the “deep” end. Dogs respond well to that, not to being pushed into “water over their heads.”

It’s very important “while the re-training is going on to avoid the real situation as much as possible,” Ms. Cottam says. That is, try not to walk your dog where other people may approach from the opposite direction “for real” because it will dilute the effect of the purposefully orchestrated, gradually closer encounters you’re staging. “It’s too hard for the dog to learn anything in the real situation,” Ms. Cottam points out, “even if you’ve got the food treat ready.” Only after you’re confident that the dog can accept the surprise of a stranger’s appearing on the street should your pet “go back into the real world,” she comments. It may take a while, but if you are patient, you really do have a very good chance of seeing changes in her behavior.

Variations on the theme

There are a number of strategies related to the one described above, all of which could work depending on how your dog responds.

Every approach must include the desensitization — letting the dog know that you will protect her from what she considers harmful rather than force her into a frightful situation willy nilly. But the reconditioning may take different forms. In the example we described above, the treat is the bait, so to speak. But for dogs who are not food motivated, or who are so food motivated that they would be too distracted to learn what you’re trying to teach them with a food treat, a squeaky toy or tennis ball might work better. Some dogs can be wonderfully satisfied by the mouthy feel of a toy or ball, the fun “grrr” of a little tug-of-war between the two of you, and would see your offer of a little bit of playful interaction as a terrific thing that happens every time a stranger approaches from some distance. Your pet would begin to make the feel-good connection that “stranger equals toy time.”

There are also positive punishment and negative punishment for trying to recondition a dog. Positive punishment — giving the dog a physical or aversive correction — we never endorse. This would include things like yanking on a choke chain, speaking harshly, and so on. Negative punishment — refusing to reward your dog when she doesn’t follow through on your directions — may be appropriate in certain instances when your dog is acting pushy, but it wouldn’t work when your dog is being aggressive out of fear. Examples of negative punishment would be refusing to give your dog a food treat or toy for not remaining calm when a stranger comes toward her. But as with positive punishment, that would prove useless for a dog who’s afraid. In fact, it could actually cause her to become more aggressive — the very thing you’re trying to get her to unlearn.

Desensitization combined with counter-conditioning that’s reinforcing, on the other hand, has a good chance of working well. But don’t underestimate the commitment. It takes time and patience to stage “safe” encounters with fearful objects or beings. It might take a few months, in fact, and if the problem is, say, the vacuum cleaner, you’ll have to vacuum during the re-training while someone else takes the dog on a walk.

If a dog cannot eventually be coaxed through her fear — some dogs are that frightened — you may want to consider medications to tamp down her undesirable reaction, or at least to get her over the rough spot while she’s re-learning. It’s not the happiest solution, but it’s there for those who need it.