Margery Coombs of Belchertown, Massachusetts, is frustrated, and with good reason. She loves her six-year-old Shetland sheepdog, Tralee, who she says “is well trained overall” and even “competes in agility,” but “is very reactive to all moving objects: bicyclists, cars, and snow-blowers,” to name a few.

“Generally,” says Ms. Coombs, “when walking near a road, we make her sit whenever a vehicle approaches. She will usually comply — and is rewarded — unless the vehicle is loud or she is already excited. Then a firm hand on the leash is all that keeps her from disaster. Walking near a busy street is not possible because we either make no progress (stopping and saying “Sit” all the time), or she is pulling every which way. Fortunately, there are many good places to walk in our area that are away from cars, but I would like to improve her reaction to moving vehicles, both for safety reasons and to give us more options.”

Ms. Coombs, we feel your pain. Many of us at the Cummings School love dogs who love to chase. “It’s a common problem,” says Tufts animal behaviorist Stephanie Borns-Weil, DVM. “And it’s why, in the old days, when people let their dogs out by themselves, so many of them were killed. When I was a veterinary student, I once saw a dog who had been hit by a snow plow and was in the ICU for several weeks.

“With a dog that’s got this herding/chasing thing going on, the desire to chase after moving vehicles is very, very hard to suppress. If you’re going to try counter-conditioning with a treat, you’ve got to find something that’s even more rewarding than the behavior. But when the behavior is hard-wired, as it is in so many breeds, there’s often nothing more rewarding than that. For a Shetland sheepdog, who has what the American Kennel Club calls ‘herding heritage,’ you can cut up pieces of steak and feed them to your dog in the street, but she’d probably still rather chase a car than stop to eat. That’s what you’re working against. The reward of the chase is greater than any possible reward an owner could offer. Still, there are ways you can work to blunt the desire to act on instinct.”

Solutions that work—if you keep expectations reasonable

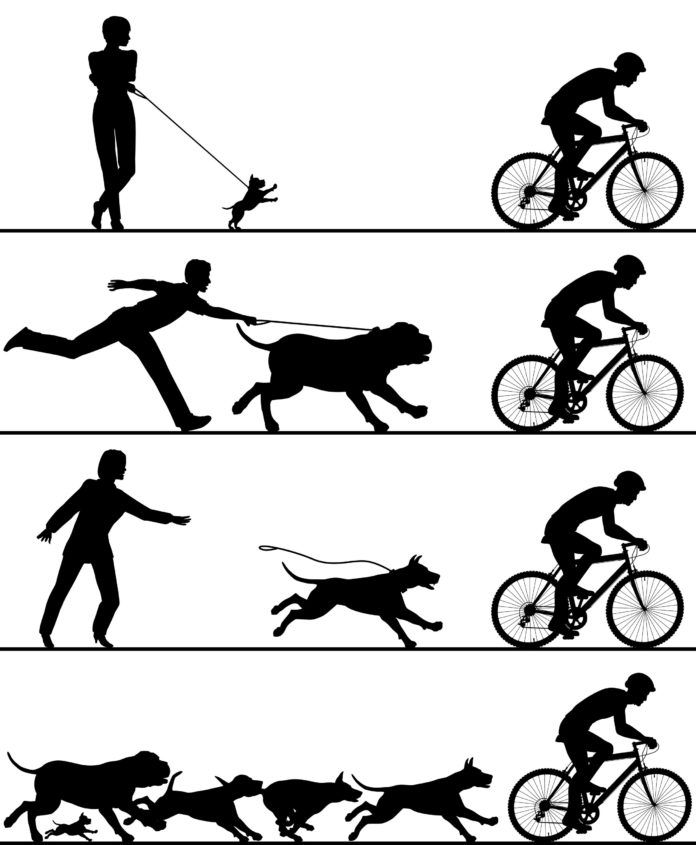

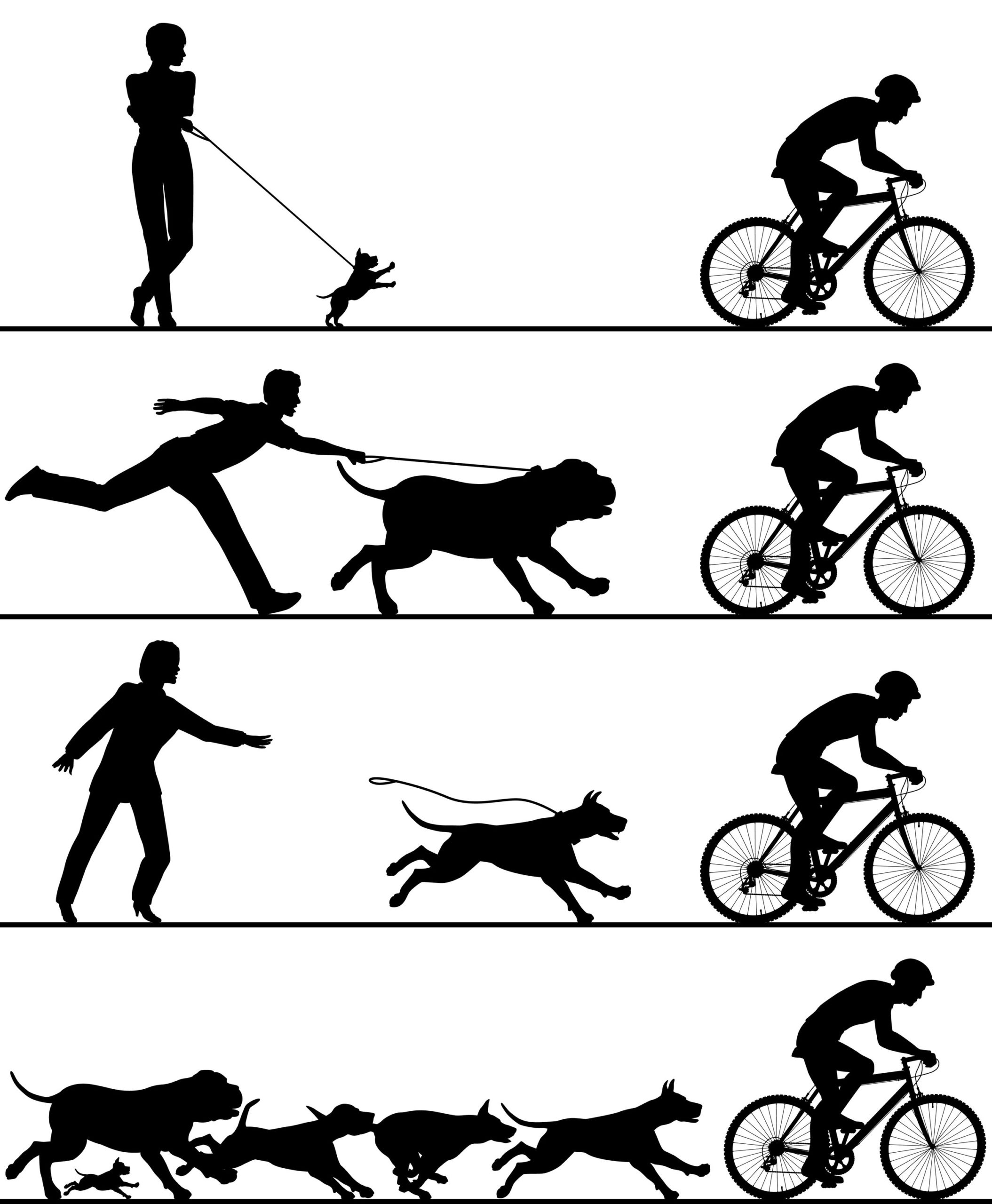

First off, be aware that if a dog has a herding instinct, you’re probably always going to have to keep her leashed when you’re walking near or along roadways. But you can help stop her from always being so reactive, thereby making life safer by insuring that you don’t get pulled along to the point of falling.

Bigstock

In the January issue, we suggested using a body harness instead of a flat buckle and collar because when you gently tug on a harness, it’s like a firm hand on the chest. But if your dog is not a short-nosed brachycephalic breed, a head halter such as a Gentle Leader will work better. A head halter shuts down the unwanted behavior even more effectively, Dr. Borns-Weil says. With a head halter, you can gently but firmly stop the chasing behavior without being dragged along in the process. It puts you in control of the situation and makes you an effective ‘dog parent.’

Counter-conditioning will help, too. That’s what Ms. Coombs is doing by getting her dog to sit when a car passes — conditioning her, with rewards, to act in a way that is completely incompatible with lunging after a car. After all, you can’t sit for a treat and chase a car at the same time. But, as Ms. Coombs says, stopping to make her dog sit every time a car passes gets tedious.

It’s for that reason that instead of the “Sit” cue, Dr. Borns-Weil recommends the “Leave it” cue. If the dog doesn’t lunge while walking (which she cannot do if you gently tug on the head halter), she has “left it.” She can get told enthusiastically that she’s a good girl and receive her delicious treat as you keep going. After a while, she’ll get the hang of it. It won’t have to be a theatrical production every time, and you won’t always have to give the treat.

“Start teaching your expectations of your pet in a low-arousal setting,” Dr. Borns-Weil advises. Go to a fairly quiet road and “stand far enough away from the curb so that your dog does not become hyper-aroused to the point that she cannot accept the treats. That will help decrease reactivity in a step-wise fashion.”

Over time, Dr. Borns-Weil says, you may even reach the point that you can go right up to the side of the road without your dog reacting when cars pass. The unwanted behavior “will actually start to become extinct.” If you let her off the leash, the doctor warns, all bets are off — she would probably still chase a car. Off the leash is an entirely different set of circumstances that leaves out any tactile input from you — an entirely different context from the dog’s point of view. But at least your pet will finally get the message not to make a big fuss every time a car passes.

Other deterrents

A dog who chases — cars, joggers, whatever — doesn’t just need a head halter and some tasty treats. She needs plenty of exercise and stimulation away from roads. It is great that Ms. Coombs takes Tralee for agility courses. She might also want to enroll her in some herding classes so she can act on her genetically encoded instinct. Imagine insisting that an ant not help to build an ant farm or that someone born with a green thumb not be allowed to garden. Without an appropriate outlet, there’s going to be inappropriate spillover one way or another. The exercise and stimulation afforded by herding courses might be just what Tralee needs to “get it out of her system.” Even just romping through the woods frequently, where no cars can endanger her, will help her to live her instinct.