“There is a lot of bad advice about separation anxiety that doesn’t work, and it results in people giving up on dogs that don’t need giving up on,” says veterinary behaviorist Stephanie Borns-Weil, DVM, who treats pets at the Tufts Animal Behavior Clinic. The dogs destroy the house in the owner’s absence, she remarks — chewing off pieces of couch cushion, destroying screens and doors, tearing up important papers — and because the strategies the owners have been told to employ fail, they think their dog is a lost cause.

Istock

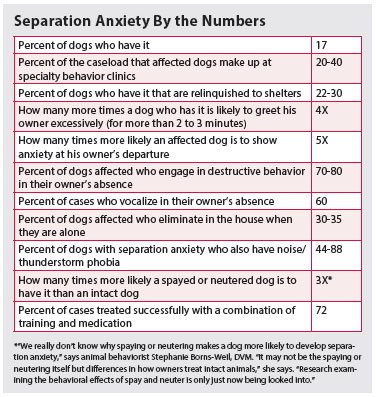

“People also end up surrendering their pets because they think their dogs are doing it out of spite” or are simply “mean” or trying to be “dominant,” she says. It’s anything but. “A dog with separation anxiety is not a mean or spiteful dog. It’s a panicked dog,” explains the doctor. “If people understand that, they bring compassion rather than anger to the situation,” and that allows them to begin to work with their pet in a constructive fashion. It’s critical, she says. “By the time people come to see us with their dog suffering from separation anxiety, the bond between the two of them is already so attenuated because the dog has destroyed the house, or the owners are going to lose their apartment from the mess or the constant barking when they’re not home. It’s at that point the story of a broken human-animal bond that needs to be healed. It’s also a serious animal welfare issue because so many dogs with separation anxiety are relinquished to shelters.”

Fortunately, says Dr. Borns-Weil, there are effective measures for getting a dog past separation anxiety. “I see it a lot,” she states. But it takes patience. “I had a turnaround with one dog, a rescue, that took 7 months,” she relates. “The dog needed multiple medications and a very intensive program. But the level of dedication that the owner brought to his dog was phenomenal. The dog is now stable.”

Herein, the ins and outs of separation anxiety — and what it takes to help a dog learn to cope in your absence.

What it is, when it strikes

Simply put, separation anxiety is severe emotional distress that occurs in the absence of group members. Not surprisingly, it’s a phenomenon of social animals like dogs (and people). In the three-headed monster of fears that can befall a dog — fear of living things, fear of inanimate objects, and fear of certain situations — it falls under the heading of a situational fear.

The underpinnings are believed to be both genetic and social in nature. The genetic aspect may be a by-product of dogs’ domestication. The social component could potentially be anything from a rough start in life (the onset of separation anxiety usually occurs before a dog is two years old) to insufficient socialization. It has been well established (not very surprisingly) that dogs who tend to get separation anxiety are more likely to be a shelter or formerly stray dog — perhaps one who was abandoned at some point.

Among the events that can trigger separation anxiety once the genetics and unfortunate socialization are in place: loss of a human or animal companion (“perhaps the old cat dies, and you never realized that the cat actually meant something to the dog,” Dr. Borns-Weil says); a move, or moves; a change in the owner’s schedule (a police officer now works the night beat); being boarded; hospitalization; and the first time a dog is left by himself.

Signs of separation anxiety are both behavioral and autonomic. Behavioral changes include destroying household objects (chewing relieves some of the stress); excessive vocalization; inappropriate elimination (both urination and defecation); excessive grooming (to the point of creating severe lacerations on the skin); escape attempts that lead to broken teeth and nails; and in some cases as the owner leaves the house, aggression or hiding. Autonomic changes consist of trembling, panting, hyperventilation, and rapid heart rate.

Signs you may not interpret as part of separation anxiety but that many dogs with the problem experience: circling, jumping, excessive vigilance, and depression.

Most dogs with separation anxiety display the telltale signs within 10 minutes of their owner’s departure, with an average time of just over 3 minutes. Of course, you won’t see these signs, even though they happen every time you leave. You’ll just see evidence of them: a destroyed house, disgruntled neighbors who tell you to quiet that yapping dog and threaten to call the authorities, urine or feces on the carpet, and so on.

What doesn’t work

There are some classical treatments for separation anxiety, and they are part of what break the bond between owner and dog and end in the dog being sent away. Don’t engage in them, even if any of them are strongly advised for your dog. They simply do not work and are classical only in the sense that they tend to be what’s recommended.

Desensitization to pre-departure cues. This three-step trick involves a) making a list of the cues that you will be leaving the house; b) mixing up the cues so that they are not associated with your departure (for instance, if you normally eat breakfast and then shower and dress, switch things up by showering and dressing and then having breakfast); and c) avoiding cues when departing (don’t look in the hallway mirror one last time, or whatever). Not only does this not work, it aggravates an already difficult situation. Dogs learn other cues that you’re about to leave — they watch your every move very assiduously — or they become anxious all the time because now they can’t predict when you’re going to leave.

Gradually increase the length of your absences. With this approach, the dog is not supposed to be left alone at all during the training period, except as part of the program. Departures should be planned and must look and feel exactly like real departures. If you always shave before you get dressed and leave in the morning, you’ve got to shave and get dressed before walking out the door. The idea is to start with short departures of just a couple of minutes and gradually increase the time away. In addition, the time away should not be lengthened linearly but irregularly — 5 minutes one time, then 2 minutes, then up to 7 and down to 6. Your return to the house should occur only when the dog has been quiet/not shown anxiety for at least 3 seconds. The problem here: it’s simply too hard to do. Compliance is impossible. Moreover, there’s no hard evidence that it does the trick.

Punish your dog for acting out during separation from you by ignoring him or reprimanding him. That so-called solution is guaranteed to make the problem worse. “Separation anxiety is pure panic,” Dr. Borns-Weil says, “not retribution or a show of dominance.” Besides, if you’ve been reading the pages of Your Dog regularly, you know that punishment is never the answer to any problem. It doesn’t teach your dog new habits; it only makes him afraid of you and breaks down the bond between you that much further.

What does work

Fortunately, there’s a four-pronged program that does help dogs with separation anxiety cope in your absence. It involves 1) what happens when you leave 2) what happens while you are away 3) what happens when you return, and 4) what happens when you and your dog are both home.

When you leave. The first order of business is to break the dog’s cycle of anxiety over your going out of the house. One way is to make sure the dog is not alone during your absence. Bring him to doggie day care, or day board him at a veterinary hospital or bring him to work with you, if possible. True, that won’t take down his separation anxiety at the root, but it sure will help him feel a lot better.

Another approach, if bringing him somewhere while you are out of the house all day is not possible, is to make sure you give him lots of exercise in the morning. By “lots” we don’t mean taking him on a 20-minute walk instead of a 5-minute walk. We mean engaging him in a vigorous game of Frisbee or throwing a ball around for him at the park — really raising his heart rate and tiring him out. That will decrease his agitation and make him more likely to rest in your absence rather than fret.

In addition, do not put his morning meal in a bowl just before you walk out the door. He is less likely to eat it if that’s his preeminent cue that he’s going to be alone all day, and if he’s hungry (and doesn’t realize it because he feels so anxious), that’s only going to make his mood worse. Think of your own mood when you’re so upset you can’t eat, even though you know you should.

Finally, as you leave, do not communicate worry or sadness to your pet about his being left home alone. That only lets the dog know that what is about to happen is bad; you’re confirming his fears. Instead, be upbeat, chipper: “See you later, Pal. Watch the house.” Give him a quick rub on his back rather than a soulful stroking of his muzzle.

Istock

While you are away. Here’s where some good old counter-conditioning comes into play, replacing an undesirable response (fear) to a stimulus (being alone) with a favorable response (contentment). This entails preparing a highly enriched environment for your dog to enjoy in your absence. Boredom is not the reason for separation anxiety, but keeping busy can really blunt its effects. Think about the fact that when you’re not there, it’s “like sitting in the middle seat on a long flight with no electronics and nothing to read,” says Dr. Borns-Weil. If a dog is nervous about your absence to start with, having all that time to just think is only going to make him more nervous.

The environmental enrichment should appeal to all five senses, starting with taste. Don’t just put the dog’s food in a bowl for him to scarf up in less than a minute or two. Make him work for it by putting it into a Kong or puzzle toy. Leave treats cleverly hidden, too, such as frozen peanut butter in a (small) Kong. That is, make eating something of an enticing scavenger hunt.

To engage the sense of smell, add novel scents like vanilla and anise to toys to make them more interesting. Some pets like hunting dog-training scents: squirrel, rabbit, duck, deer. Mmm…..

Your dog’s sense of sight can be tickled with access to a large window that will widen his view. And you can make the view more interesting by, say, hanging a bird feeder to attract both birds and squirrels.

Is there a possibility for a doggie door that will let him into the backyard for more variety in seeing and exploring? That will most definitely attenuate his anxiety about being left alone, in part by making him feel less trapped in “solitary confinement.”

Avoid silence. Keep your dog’s hearing in use with the television or radio on in the background. Silence equals “tick tock tick tock” all day long.

Finally, appeal to your dog’s sense of touch by preparing a comfy, soft resting place, such as a well padded bed or an (open) crate with a wonderful quilt that he loves.

When you return. Keep greetings upon your arrival back home low key. If you act every day like you are coming back from a 3-month Grand Tour of Europe, your dog is going to get the message that your having been away is a very big deal because your coming home is such a big deal. Just fold it casually into the day’s events.

Also, wait at least an hour before you serve the evening meal. The dog should not associate your coming back with one of his basic needs (just as he should not associate your leaving with that need). That will only serve to elevate the significance of your having been gone.

When you’re both home. When you’re not just coming in or just about to leave, reward calm, independent behavior. Tell your pet what a good boy he is when he hangs out without whining; perhaps stroke him or give him a delectable treat. At the same time, ignore demanding, attention-seeking behavior. That will help your dog learn that standing on his own four paws is what gets him your approval and all the good things in life.

Do keep the environment enriched when you are home. You can’t just go about your business all day and leave the dog to lie around like a throw rug. Play with him, take him for a romp or a game in the park, get together with other owners and their dogs, mix it up. That will not make your dog more miserable in your absence. It will strengthen your bond and thereby calm him.

Adding medication to the mix

It’s certainly possible to get your dog past separation anxiety by following the four-step program outlined above. But there’s a greater chance of success if you also use medication to help calm your dog as he learns to live “without you.” Then, too, there’s the time factor. As Tufts Animal Behavior Clinic Director Nicholas Dodman, BVMS, says, “you can attenuate separation anxiety without medication. The process just takes a whole lot longer.”

There are two kinds of drugs used for separation anxiety: those employed as background medication to help the dog’s mood in general and those administered as situational medicines to help the dog cope right there, in the moment.

Background medications include SSRIs such as fluoxetine (Prozac), as well as the anti-anxiety agent buspirone (Buspar) and the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine (Anafranil). Depending on the drug, there’s a latency of 2 to 6 weeks, so do not look for immediate changes in mood.

Situational medications include clonidine, propranolol (which reduces sweating on paws and panting), trazodone, and alprazolam (Xanax), a classic relaxation drug, or “chill pill,” says Dr. Borns-Weil. All of these reduce epinephrine and thereby blunt the panicked sensations of the fight-or-flight syndrome experienced by dogs with separation anxiety. They take about 2 hours to take effect, so you have to plan accordingly. Don’t give them the minute before you walk out the door.

The upshot

On a certain level, it’s easy enough to ascertain whether the program is working. If you come home and the house is not ripped apart, the dog has not relieved himself on the floor, and neighbors are not talking to you about excessive barking (the three major complaints of separation anxiety), you can feel pretty confident that the plan you have put into place, perhaps with medication, is having a beneficial effect. But to be certain beyond the shadow of a doubt, go the extra mile: set up Skype or a webcam or Face Time to see what your dog is actually doing while you’re away.

It’s probably best, Dr. Borns-Weil says, to think of separation anxiety as “going into remission” rather than being “cured.” Relapses happen, and at those times you need to redouble your efforts. “I’ve seen it after Christmas time,” she comments. “People are home a lot, the kids are off from school — there’s a break in the routine that keeps everyone together. Then the dog is expected to go back to staying home alone after New Year’s, but he’s kind of barely hanging on. He has become to used to people always being around, even for only a week.”

The bottom line: yes, there’s a great chance of success when it comes to taking separation anxiety out of the picture. Some dogs, in fact, can even stop using medication. But that doesn’t mean the problem disappears. It can be reignited, so to speak, and owners should, if necessary, be prepared to go through the paces once again.